Coproduction in Municipal Education Councils: possibilities for the coproduction of control

Coprodução em Conselhos Municipais de Educação: possibilidades para a coprodução do controle

Coproducción en los Consejos Municipales de Educación: posibilidades para la coproducción del control

Flávia Antunes Souza Paula Chies Schommer

Highlights

The essay examines the activities of Brazilian Municipal Education Councils through Municipal Education Plans.

It highlights the Municipal Education Councils and Plans as instruments for the coproduction of control.

The essay provides insights for future studies combining education and public management through the coproduction.

Abstract

This essay aims to theoretically examine the actions of Municipal Education Councils in coproduction arrangements through Municipal Education Plans and coproduction of control. These councils are spaces conducive to the coproduction of control since their formative nature, functions, and attributions lead to mutual and continuous engagement between public agents and citizens to perform and control education services. This theoretical essay provides insights for future studies integrating the education and public management fields and addressing the coproduction of this public good.

Keywords

Coproduction of the public good. Coproduction of control. Municipal Education Council. Municipal Education Plan.

Received: 12.29.2022

Accepted: 05.09.2023

Published: 06.02.2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.26512/lc29202346460

Introduction

The coproduction of the public good is a strategy to produce public goods and services in a network, with the engagement of citizens, governments, and organizations that work in the public sphere (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2007; Salm & Menegasso, 2010). In spaces of dialogue and shared practices (Schommer et al., 2012), providing public services becomes a process of social construction (Bovaird, 2007) in which the state and society work together to respond to public problems.

Citizen participation is one of the structuring elements of coproduction (Rocha et al., 2021) and can be understood as a link between coproduction and education. Democratization of education means the participation of different social actors in the planning and execution of services, engaging not only professionals working in the school environment but parents, students, and the community (Mendonça, 2004). This is the case, for example, of the management councils, “institutionalized spaces of social participation” (Rocha, 2008, p. 137) in Brazil that allow for a rapprochement between society and local government for cooperation in public activity. They do so through instruments such as Education Plans.

In education, the theoretical contribution of coproduction includes studies such as Ostrom (1996) in Nigeria, and Pestoff (2006), in European countries. Education coproduction research prioritizes schools and communities providing and delivering services collaboratively (Brand & Rolland, 2018; Jakobsen & Andersen, 2013; Mathews, 2008). On the other hand, studies on the coproduction of control coproduction focus on collaboration between institutionalized control agencies, civil society organizations (CSOs), and citizens involved in social accountability (Doin et al., 2012; Schommer et al., 2015).

This essay focuses on the locus of social participation in the Brazilian Municipal Education Councils, or CMEs. According to Miola and Costa (2019, p. 4), these arrangements provide “propitious spaces to put this democratic perspective into practice.” CMEs serve as public forums for participation, discussion, deliberation, debate, and control (Ronconi et al., 2011). Therefore, this work aims to theoretically examine how CMEs can engage in coproduction through Municipal Education Plans (PMEs) and the coproduction of control.

From the perspective of coproduction, CMEs play a crucial and unique role as they provide spaces for dialogue and collective construction to address public education demands. They facilitate the development of education plans, reports, manuals, assessments, and monitoring tasks (assigned to or proposed by them) related to the delivery of educational services.

The members of CMEs are representatives of students, parents, public servants, education professionals, specialists, and neighborhood associations. They are democratically elected or appointed and are entitled to carry out a set of activities in the field of municipal education, both public and private. Their functions can be grouped into normative, consultative, deliberative, supervisory, mobilizing, and propositional dimensions (Miola & Costa, 2019). From the theoretical and normative point of view, several of these functions are subject to coproduction.

The social accountability put forward by CMEs involves various actors and instances of society in the demand and construction of public information that subsidizes debates, deliberation, and management monitoring in education. The coproduction of information and control occurs when there is an interaction between social accountability and institutional control bodies and mechanisms. In this case, citizens and professionals mutually exercise socio-political control over public administration (Doin et al., 2012; Schommer et al., 2015).

Research on CMEs reveals a gap in understanding their role in the design and delivery of public services. Certain functions they perform suggest an opportunity for studies that explore CMEs as spaces where practices of coproduction, particularly in the context of coproduction of control. Therefore, combining studies on coproduction in the field of education with studies on coproduction of control is worthwhile. One example of this convergence is visible when CMEs define goals and indicators while elaborating PMEs and monitoring their implementation.

This work is a theoretical essay, which is a type of scientific production that allows for an open and intersubjective debate. It acknowledges the subjectivity of the essayist and enables the interlocutor to formulate new questions and understandings about the phenomena being presented (Meneghetti, 2011). The theoretical foundation of this work is based on a narrative review of coproduction of public goods and services, coproduction of control, CMEs, and PMEs. The review encompasses scientific articles and documents, both normative and descriptive, produced by public agencies. Additionally, a systematic review on coproduction in education was conducted between February and March 2022. This review considered studies found on the databases Ebsco, Emerald, SciELO, Science Direct, Scopus, Spell, and Web of Science,” by using the search descriptors (“coproduction” OR “coproduction” OR “coproducer” OR “co-producer”) AND (“education” OR “educational” OR “school” OR “teaching”) in the title, abstract, and keywords fields, without a specific time frame.

The essay is presented as follows: after this introduction, the following section addresses the coproduction of the public good, with debates on coproduction in education and the coproduction of control. After, there is an overview of CMEs and PMEs, followed by a discussion that links these concepts and the final considerations.

The coproduction of the public good

The coproduction of the public good involves the regular and ongoing involvement of professionals and citizens in the provision of public services (Pestoff, 2006; Bovaird, 2007). Studies such as Brudney and England (1983), Ostrom (1996), Bovaird (2007), Pestoff (2006), and Alford (2014) understand that, in coproduction, public services are not solely provided by professionals and public agencies but also by citizens and communities.

The discussion on coproduction entails a reinterpretation of the formation and delivery of public policies and services to users (Chaebo & Medeiros, 2017). The provision of public services can be understood as a process of social construction where actors within self-organizing systems negotiate rules, norms, and institutional structures, rather than accepting the rules as predefined (Bovaird, 2007).

When associated with democracy, coproduction is based on meeting “society’s demands for increased transparency, efficiency, participation, and social accountability” (Moretto Neto et al., 2014, p. 165). It requires the organized and permanent involvement of citizens, directly participating in the production and delivery of goods and services, characterized as a practical and “hands-on” approach (Schommer et al., 2015). The parties involved assume the risks (Bovaird, 2007) and establish a relationship of mutual influence (Schommer et al., 2015).

Brudney and England (1983) identified three levels of coproduction: (a) individual coproduction, where the users participate in the production of the good or service they receive; (b) group coproduction, where a group of individuals enhances the quality of services the same group receives; and (c) collective coproduction, where the benefits from continuous cooperation between professionals and users extend to the entire community.

The process occurs in two main stages: the co-design or co-creation stage, in which citizens and professionals act together in planning activities or services, and the co-delivery stage, where they collaborate to implement those plans or deliver the services (Bovaird, 2007; Brandsen & Honingh, 2015). Moreover, authors such as Nabatchi et al. (2017) subdivide planning into two stages (co-commissioning and co-design) and implementation into two others (co-delivery and co-assessment), emphasizing the peculiarity of the evaluation stage.

Coproduction requires an agile service bureaucracy and participatory citizenship, recognizing traditional forms of citizen participation in service delivery. These forms include involvement in advisory and review boards, participation in public hearings, and cooperation in surveys where the population evaluates government performance (Brudney & England, 1983). It is different from volunteering because in coproduction, the individuals involved in the execution also benefit from the process (Verschuere et al., 2012).

Coproduction differs from public consultation and public participation, which are communication processes that often emphasize decision-making (Loeffler & Bovaird, 2016). Coproduction, on the other hand, focuses on “the direct input of citizens in the individual design and delivery of a service during the production phase” (Brandsen & Honingh, 2015, p. 428). We understand that both types of action can be observed in municipal councils.

The development of coproduction arrangements is a more complex task compared to its theoretical demonstration, as it requires resources that may not always be readily available and investments from the participants themselves (Verschuere et al., 2012). The quality of such arrangements becomes evident in each context through repeated interactions and the ongoing engagement of users (Chaebo & Medeiros, 2017). This also applies when it comes to councils.

Coproduction processes demand and depend on integrating elements such as transparency, information, trust, participation, and accountability, which can be considered structuring elements of coproduction. Such elements are sometimes presented as necessary conditions, sometimes as consequences of coproduction, and can be reinforced, transformed, expanded, or destroyed during the process (Rocha et al., 2021).

The coproduction of public services, such as healthcare, education, or public security, contributes to strengthening social accountability activities since “citizens can coproduce public goods and services by directly participating in their production and/or adopting an attitude of surveillance at all stages of the process” (Schommer et al., 2012, p. 236). Thus, coproduction is also justified by the fact that the contribution and pressure exerted through social accountability activities on the design and delivery of public services can enhance the accountability of these processes (Rocha et al., 2012).

In the field of education, Rostirola (2021) observes that accountability principles have been disseminated in several countries, transcending their economic-related aspects. In this direction, Brazilian states and municipalities have been striving to comply with national or international assessments by developing their own accountability mechanisms.

In this context, it is worth examining how coproduction manifests in the field of education. To explore this further, we conducted a systematic review of coproduction in education and identified nineteen studies: Davis and Ostrom (1991), Ostrom (1996), Bifulco and Ladd (2006), Matthews (2008), Blasco (2009), McCulloch (2009), Paarlberg and Gen (2009), Carey (2013), Jakobsen and Andersen (2013), Radnor et al. (2014), Suslova (2016, 2018), Jivan and Barabas (2017), Brand and Rolland (2018), Soares and Farias (2018, 2019), Honingh et al. (2020), Cicatiello et al. (2021), and Oliveira and Mendonça (2021).

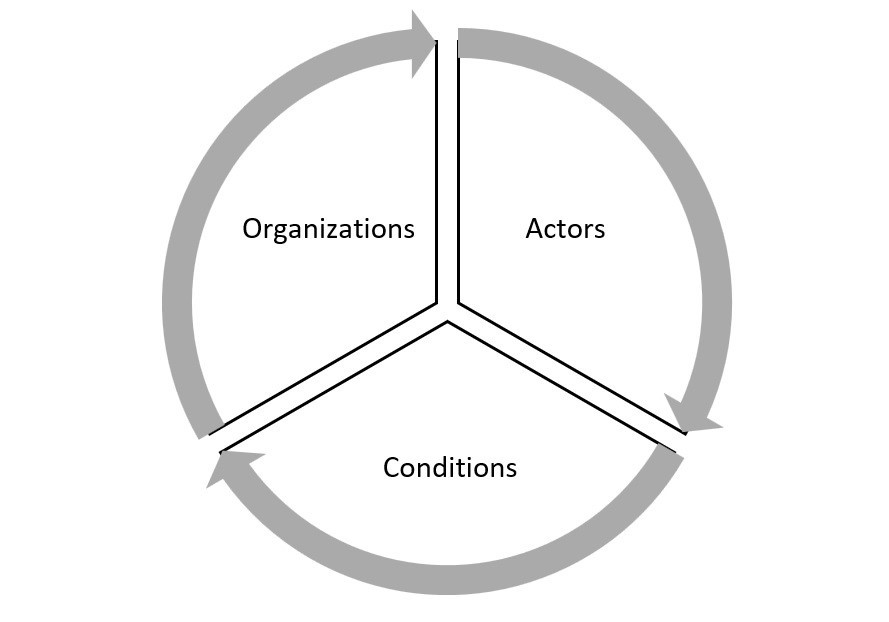

The studies discuss and offer evidence on (i) the nature of education and its provision systems by public and private organizations; (ii) the interaction of the community, families, and students with professionals in the field, in order to design and provide services; (iii) conditions that favor or hinder coproduction. In each study, there are interfaces between these three aspects, and it is possible to propose three analytical dimensions for the study of coproduction in education, summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1

Dimensions for the study of coproduction in education

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The works mentioned above include empirical research involving different types of participants (actors dimension), approach various institutions and discuss topics regarding different educational levels (organizations dimension), and present facilitators and obstacles for the production and/or delivery of services in education (conditions dimension). A gap identified in the studies was on the roles of the councils in the coproduction of education, considering that their peculiarities can add elements to the proposed analytical dimensions (actors, organizations, and conditions) and enrich the debate.

The coproduction of control

The coproduction of control refers to the engagement and continuous interaction of various actors and mechanisms of institutional control and social accountability, formally and informally, to produce public information and use them in the socio-political control of public administration (Doin et al., 2012; Schommer et al., 2015).

Just as “the control by citizens over the government is a fundamental public good for the constitution of a just and democratic society” (Doin et al., 2012, p. 57), one can conceive “coproduction of control as a public good” that serves the public interest (Rocha et al., 2012). This is because accountability can be more effective when there are continuous interactions between actors and mechanisms of institutional control and social accountability rather than relying solely on isolated actions.

Accountability depends on citizen participation and qualified information available to society (Rocha et al., 2012). Although public information is traditionally produced by government agencies, citizens and CSOs can engage in its production and dissemination, for example, to monitor political promises (Doin et al., 2012), to counteract and complement information, and to support collective debates and decisions.

However, producing information within the scope of public administration is not easy. It demands basic conditions such as “organization, structure, technical capacity, specialized personnel, and legal competence.” Coproduction can contribute to this process precisely due to the involvement of society (Rocha et al., 2012, p. 4).

Therefore, the generation and use of information can and should be carried out by actors who work in the public sphere, requiring “spaces for dialogue and coordination around shared practices” (Schommer et al., 2012), characteristics identified in institutional spaces of education.

Due to its practical and collaborative nature, the coproduction of control is related to social accountability, an approach to fostering accountability based on the engagement of ordinary citizens and CSOs, who participate directly or indirectly in the accountability process (Hernandez et al., 2021). Social accountability mechanisms can be initiated or supported by the state, citizens, or both, and they often operate in a “bottom-up” fashion, driven by demands from the community (Foster et al., 2004). Social accountability is collaborative and closer to services at the street level, aligning with the hands-on nature of coproduction.

In the field of education, this can be observed in the involvement of students and the school community when they contribute to the production of information and control in the environments where they operate. For example, in the Brazilian state of Goiás, the project “Estudantes de Atitude” encourages public schools in the state, through gamification, involving practices related to transparency, social accountability, volunteering, and corruption prevention (Goiás, 2022). In Portugal, the initiative of implementing a participatory budget in schools (República Portuguesa, 2017) encourages primary and secondary school students to develop proposals that contribute to improving the schools’ infrastructure or the teaching-learning process, engaging in the development of part of the budget and monitoring its execution (Dias & Júlio, 2019). In the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, the school community in the municipality of Anita Garibaldi participated in an operational audit carried out by the state’s Court of Auditors (TCE-SC), debating issues of infrastructure, school transport, school meals, appreciation of teaching professionals, and democratic management in municipal education (Pestana et al., 2020).

The Brazilian education councils, according to the theoretical discussion below, prepare, gather, discuss, and systematize information to support decisions, plans, and inspection activities, exercising social accountability and coproducing control with other public administration agencies, particularly in the local government scope.

Municipal education councils in Brazil

The CMEs are assemblies of a public nature and based on popular participation. These arrangements were developed “to advise, issue an opinion, deliberate on issues of public interest in a broad or narrow sense” (Lima et al., 2018, p. 329).

According to Bordignon (2010, p. 1), the councils find their essential nature and primary function in the mediation and negotiation between society and the government, working to advance collective interests.

The discussion about CMEs in Brazil includes movements that seek to overcome the “colonial legacy of the centralization of power,” considering the capacity of the people in the local community to participate in decisions about their lives (Lima et al., 2018, p. 328).

The functions of the CMEs that stand out are i) normative: elaboration of rules to be adapted in municipalities, following determinations of federal and/or state laws and complementary norms; ii) deliberative: authorization or not for the operation of public and private schools, in addition to the legalization of education programs and deliberation on the curriculum in the local education system; iii) advisory: answering the questions and doubts of the government and society, issuing formal opinions; iv) supervisory: monitoring the policy implementation and evaluating the municipalities’ results in education (Todos pela Educação, 2018).

The CMEs are responsible for many activities. Miola and Costa (2019) highlight i) consultation with society regarding the needs and priorities to be considered in the formulation of local education policies, ii) enabling the plural participation of society in the planning, formulation, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of education policies; iii) follow-up and control of acts performed by managers; iv) follow-up of the PME’s implementation; v) inspection of the PME’s compatibility with the National Education Plan; vi) monitoring of budget items to identify forecast actions set out in the Education Plan; vii) follow-up and inspection of the application of resources arising from agreements, donations, and other transfers destined to the public and private actors dedicated to education; viii) inspection of the implementation of the National Common Curricular Base. Attributions iii) to viii) detail the supervisory function, which we consider the core of the coproduction of control.

CMEs are established in Brazilian municipalities by a specific municipal law supported on provisions of the 1988 Federal Constitution (Brasil, 1988), Law 9.394 of December 20, 1996 – which establishes the Guidelines and Bases of National Education (Brasil, 1996) – and of the National Education Plan – as a strategy of Target 19 (19.5), “stimulating the constitution and strengthening of school councils and municipal education councils, as instruments of participation and supervision in school and educational management” (Todos pela Educação, 2018).

Although CMEs derive from national legislation and norms, they are not mandatory. The local government’s decision to pass the law creating these councils comes from community mobilization and requires a formative and informative process about the CME’s importance and role in the municipal education system (Bordignon, 2010). The legislative process starts with the local executive elaborating and sending the bill to the City Council. The legislative body analyzes and may propose ammendments. After passing the bill, it returns to the executive for the mayor’s sanction. Depending on how the local law is designed, the CME’s members are appointed or chosen through elections. The first activity of the council members is to draw up an activity plan. The local government has to offer infrastructure to enable the CME’s continuous activities, including the provision of training, administrative staff, and support from the Municipal Education Department (Todos pela Educação, 2018).

These councils are present in 4,771 Brazilian municipalities (86% of them). Municipalities that do not pass a law creating CMEs must resort to State Education Councils, which play similar roles at the state level and can assist the local education systems (Todos pela Educação, 2018). CMEs may present different forms of constitution and operation. Their profile should be is defined after a broad debate in which the government and the mobilized society define the structure, coordination, composition, functions, and attributions (Bordignon, 2010).

The CME’s members are representatives of the local government, the school community, and civil society in general, usually including staff from the Municipal Education Department, teachers, school managers, and employees working in the Municipal Education System. Religious entities, non-governmental organizations, foundations, and companies can also participate. This collegiate must have its full members with their respective alternates, in a number determined according to the local reality (Miola & Costa, 2019).

Each council member is expected to offer their perspective on the public good, aware of their role and the priorities on which they must act. They are expected to study and understand their function and tasks, satisfactorily representing the population that, in turn, offers them feedback (Lima et al., 2018).

CMEs may be considered as institutional spaces that favor coproduction of control since they are “traditional forms of citizen participation in service delivery” (Brudney & England, 1983, p. 62), which represent a form of coproduction, and because one of their functions is controlling the governments’ activities in education. The CME is an arrangement gathering a diversity of actors, and the activities performed range from the formulation to the implementation of policies (Pestoff, 2012). These characteristics reinforce the alignment with coproduction, in its different stages.

CMEs contribute to controlling municipal education management and, when operating properly, become a reference for democratic management, relying on civil society in decisions and implementation of educational policies and services. Together with the state and national education councils, CMEs are participatory institutions for the democratic management of public education. One of the main tools to pursue this end is the PMEs discussed in the next section.

Municipal Education Plans

For the democratic management of education, the creation and consolidation of PMEs are presented as a key element of the National Education System. These plans are an opportunity to reflect on a given reality and establish goals, strategies, and actions for municipalities to improve basic education (Cabral Neto et al., 2016).

One of the main activities carried out by the CMEs is the elaboration and monitoring of PMEs. According to the Brazilian educational policy, the PME is developed based on the guidelines of the National Education Plan, PNE. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Education, the function of the national plan is to coordinate the National Education System, SNE, fostering collaboration with states and municipalities (MEC, 2014). The National Education Plan covers a period of ten years and offers directions for the development of the State Education Plans and the PMEs, which must be aligned with the national objectives. The development of these plans requires coordination between different levels of government and collaboration between the government and society in order to obtain alignment between them. According to Fasolo and Castioni (2017, p. 593), “the PNE [National Education Plan] is not a plan by or for the Union, but rather a plan for Brazilian society, the states, and municipalities” (Fasolo & Castioni, 2017, p. 593).

The PME is a planning instrument that aims at the development of local education. It serves the objectives and purposes of the Municipal Education System, considering the national and state guidelines. It is based on principles of democratic management, autonomy, and collaboration, and the responsibilities defined in the plan are attributed according to local legislation. It is jointly implemented by the local government and civil society, ensuring the process’s political nature (Silva & Nogueira, 2014).

According to Cabral Neto et al. (2016), the municipality structures the education policy through the PME since the plan guides the authorities when defining specific targets and activities and attributing responsibilities to both the local government and the community. In addition, the PME guides the use of resources that must be applied to guarantee democracy, equality, and quality.

The PME sets short, medium, and long-term goals and covers a period shorter than the national plan. It is expected to be the outcome of a dynamic process that seeks to improve municipal education based on a diagnosis of the local reality and offering guidelines, objectives, deadlines, and evaluation criteria (Silva & Nogueira, 2014).

The Ministry of Education (MEC 2014, p. 7) presents premises regarding the PME: i) the adequacy or elaboration of the PME requires hard and organized work involving “collection of data, information, studies, analyses, public consultations, decisions, and political agreements”; ii) the PME’s alignment with the National and State Education Plans, recommending the involvement of all segments of society and the three spheres of government, coordinating the goals between the plans; iii) the PME must be a document embraced by the municipality as a whole. Therefore, it must consider all the educational needs of citizens, not only the educational services the municipality offers directly to the community; iv) intersectoriality is a strategic premise for the plan since education is a responsibility shared by all government departments, counting on the active participation of society; v) it is necessary to know the context since the effectiveness of the plan depends on understanding the demands, weaknesses, challenges, and potentialities of the municipality; vi) the PME must be connected with the other planning instruments, such as the budgets of the federal, state, and local governments; vii) the success of the PME depends on its legitimacy, being submitted to a broad debate in society.

The importance of the PME goes beyond guaranteeing a fundamental right for which municipalities have significant responsibility. The plan’s collective elaboration and implementation can potentially change how managers and the community deal with educational policies (Cabral Neto et al., 2016), allowing society to achieve more tangible results. Its elaboration and implementation can be seen as a coproduction process in education.

The implementation and monitoring stages of the PMEs enable the coproduction of control, enhancing the synergy between government and citizens. This is exemplified by the TCE Educação project, which was established in 2017 and formalized by the Court of Accounts of the State of Santa Catarina (TCE-SC), Brazil, through Ordinance TC-0374/2018 (TCE-SC, 2018). The project is a partnership involving the TCE-SC, the State Education Council, the Association of Members of the Brazilian Courts of Accounts (ATRICON), and other Brazilian courts of accounts. Its objective is to promote transparency and social accountability by encouraging, monitoring, and controlling the execution of education plans at all levels of government (TCE-SC, 2022). The partnership includes activities such as developing an index related to the Tax on Circulation of Goods and Services (ICMS) applied to education in the State of Santa Catarina, and formulating state legislation for ICMS (TCE-SC, 2022), thereby promoting the coproduction of public goods.

Discussion

As presented, the coproduction of the public good is a strategy for producing public goods and services that involve the execution of activities through the interaction between public agents and citizens. It is characterized as an approach of shared practices applicable to different areas of public management.

The systematic review of coproduction in education has shown that, to date, studies in this area have focused coproduction of the service at the street level. Empirical research presents a diversity of organizations, actors, and conditions (dimensions) involved in the school routine. However, no studies were identified regarding educational councils.

The narrative review on the CMEs allowed us to understand them as institutional spaces conducive to coproduction – both due to their participatory constitution (which includes a diversity of actors discussing and addressing educational demands) and the nature of the functions performed (which involve activities such as planning, supervision, and monitoring).

As mentioned above, the PME is one of the main working instruments of a CME. Considering its unique educational and political nature, the PME is crucial in coproduction since it requires collective elaboration, implementation, and monitoring, and the plan permeates practically all of the CME’s functions.

The evidence demonstrates the viability of coproduction of control in education with the involvement of several actors in coproduction practices – as seen in the cases of Estudantes de Atitude (Goiás, 2022), Participatory Budgeting (República Portuguesa, 2017), and in the operational audit carried out by the TCE-SC in 2022.

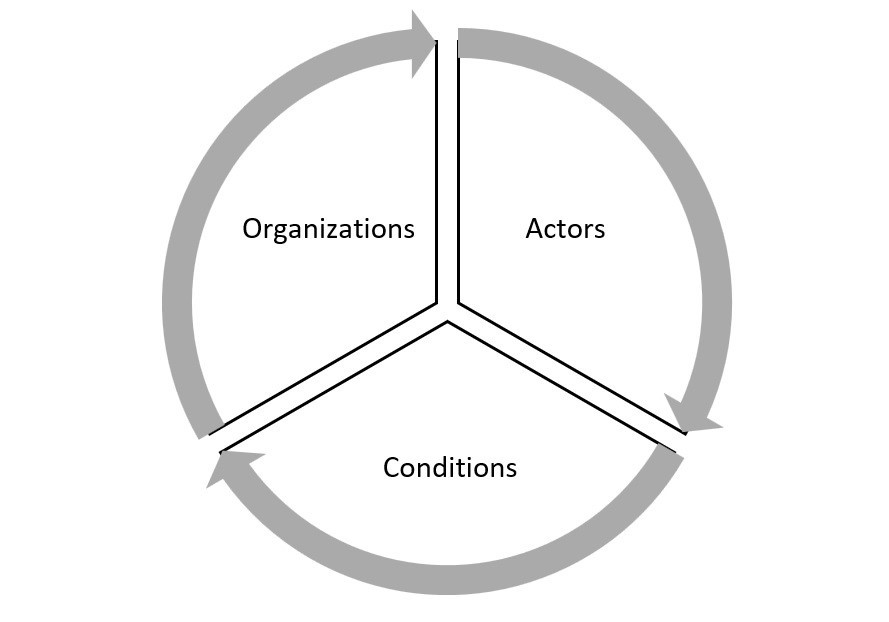

Thus, it is possible to admit that the CMEs constitute spaces for the coproduction of the public good that demand social accountability, which can be met through the coproduction of control. This requires adopting management models or mechanisms that encourage collaborative work between government and society. The PME is one of the means for this. The theoretical connections of the essay are summarized in figure 2.

Figure 2

Theoretical connections – coproduction, control, councils, and municipal education plans

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

For CMEs effectively exercise their potential regarding the coproduction of control, they have to foster citizen participation and collaborative practices engaging education professionals and professionals working in the local government and institutional control agencies. Citizens alone have limited power to exercise accountability. However, as they organize themselves in collective spaces and connect with agents and institutional control mechanisms, they qualify their participation and expand their capacity to contribute.

Final considerations

This work aimed to theoretically examine the actions of the Brazilian Municipal Education Councils (CMEs) in coproduction arrangements through municipal education plans (PMEs) and the coproduction of control.

We discussed the viability of CMEs as spaces for coproduction of control in the field of education. The relevance of these entities in the Brazilian education structure and their potential to promote coproduction of public goods and services reiterate the need for studies.

It was possible to observe that the PME is an instrument for the CMEs to engage in coproduction of control, as their collective, technical, and political nature encourages collaboration between different actors and levels of government and society by demanding actions, resources, and connection while planning, implementing, and monitoring education policies.

This theoretical essay led us to recognize limitations associated with the action of CMEs, both in the elaboration and implementation of PMEs and in coproduction in education and coproduction of control. Future studies conducting a broad literature review about these councils as participatory instances of social accountability in Brazil and empirical research addressing CMEs are needed to understand these limitations better and identify intervening conditions in the councils’ role in coproduction of control.

In addition, future research on the coproduction of control in education can examine the Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and the Valorization of Education Professionals (Fundeb) (Brasil, 2022), which is an essential source of resources for education in Brazil. The social relevance and complexity of monitoring Fundeb by society require participatory control practices, including resource collection and application supervision. Also, recent legislation regarding the transference of funds from state taxes to education has been subject to dispute between different areas of government (Peres et al., 2022, n.p.), which is a situation worth further investigation adopting the lens of social accountability and coproduction of control.

References

Alford, J. (2014). The multiple facets of co-production: building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Administration Review, 16(3), 299-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.806578

Bifulco, R., & Ladd, F. (2006). Institutional change and coproduction of public services: The effect of charter schools on parental involvement. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(4), 553-576. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3840378

Blasco, C. M. (2009). Who is the final user of the educational service? Coproduction and definition of actors and service in Colombia (1991-2006). Analisis Politico, 22(67), 207-223. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/49800

Bordignon, G. (2010). Passos para criar um Conselho. Conselho Municipal de Educação: colegiado da gestão democrática do sistema. UNCME. http://painel.siganet.net.br/upload/0000000002/cms/images/editor/files/Educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o/Manuais/Passos-para-criar-um-conselho.pdf

Bovaird, T. (2007). Beyond engagement and participation in coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 67(5), 846-860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.x

Brand, D., & Rolland, M. (2018). Case study-partners for possibility: co-production of education. Em T. Brandsen, & B. Verschuere. Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business (pp. 174-176). https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/541662

Brandsen, T., & Honingh, M. (2015). Distinguishing Different Types of Coproduction. Public Administration Review, 76(3), 427-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12465

Brasil. (1988). Constituição Federal. Congresso Nacional do Brasil. Assembleia Nacional Constituinte. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm

Brasil. (1996). Lei 9.394 de 20 de dezembro de 1996 (Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional). Presidência da República. Casa Civil. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm

Brasil. (2022). Lei n.º 14.325, de 12 de abril de 2022. Presidência da República. https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2022/lei/l14325.htm

Brudney, J. L., & England, R. E. (1983). Toward a definition of the coproduction concept. Public Administration Review, 43(1), 59-65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/975300

Cabral Neto A., Castro, A. M. D. A., & Garcia, L. T. dos S. (2016). Plano Municipal de educação: elaboração, acompanhamento e avaliação no contexto do PAR. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação, 32(1), 47-67. https://doi.org/10.21573/vol32n012016.62648

Carey, P. (2013). Student as co-producer in a marketised higher education system: a case study of students' experience of participation in curriculum design. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50(3), 250-260. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.796714

Chaebo, G., & Medeiros, J. (2017). Reflexões conceituais em coprodução de políticas públicas e apontamentos para uma agenda de pesquisa. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 15(3), 615-628. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395152355

Cicatiello, L., Simone, E. de, D’Uva, M., Gaeta, G. L., & Pinto, M. (2021). Coproduction and satisfaction with online schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from European countries. Public Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1990591

Davis, G., & Ostrom, E. (1991). A Public Economy Approach to Education: Choice and Co-Production. International Political Science Review, 12(4), 313-335. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1601468

Denhardt, R. B., & Denhardt, J. V. (2007). The New Public Service: serving, not steering (Expanded edition). M. E. Sharpe.

Dias, N., E. S., & Júlio, S. (2019). The Participatory Budgeting World Atlas, Epopeia and Oficina. www.oficina.org.pt/atlas

Doin, G., Dahmer, J., Schommer, P., & Spaniol, E. (2012). Mobilização social e coprodução do controle: o que sinalizam os processos de coprodução da lei da ficha limpa e da rede de observatório social do Brasil de controle social. Revista Pensamento & Realidade, 27(2), 56-79. https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/pensamentorealidade/article/view/12648

Fasolo, C. P., & Castioni, R. (2017). Educação profissional no PNE 2014-2024: contexto de aprovação e monitoramento da meta 11. Linhas Críticas, 22(49), 577-597. https://doi.org/10.26512/lc.v22i49.4946

Foster, R., Malena, C., & Singh, J. (2004). Social Accountability: an introduction to the Concept and Emerging Practice (English), Social Development Papers, 76. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/327691468779445304/Social-accountability-an-introduction-to-the-concept-and-emerging-practice

Goiás. (2022). Governo do Estado de Goiás. Estudantes de atitude. https://www.estudantesdeatitude.go.gov.br/2022

Hernandez, A. Q., Schommer, P. C., & De Vilchez, D. C. (2021). Incidence of Social Accountability in Local Governance: The Case of the Network for Fair, Democratic and Sustainable Cities and Territories in Latin America. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 506-562. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11266-020-00295-6

Honingh, M., Bondarouk, E., & Brandsen, T. (2020). Co-production in primary schools: a systematic literature review. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86(2), 222-239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318769143

Jakobsen, M., & Andersen, S. (2013). Coproduction and Equity in Public Service Delivery. Public Administration Review, 73(5), 704-713. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12094

Jivan, A., & Barabas, M. (2017). The Coordinates of Co-Production in the Educational Services System. Timisoara Journal of Economics and Business, 10(1), 35-50. http://doi.org/10.1515/tjeb-2017-0003

Lima, P. G., Almenara, G., & Santos, J. (2018). Conselhos municipais de educação: participação, qualidade e gestão democrática como objeto de recorrência. Revista Diálogo Educacional, 18(57), 326-347. https://doi.org/10.7213/1981-416x.18.057.ds02

Loeffler, E., & Bovaird, T. (2016). User and Community Co Production of Public Services - What Does the Evidence Tell Us. International Journal of Public Administration, 39(13), 1006-1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2016.1250559

Mathews, D. (2008). The public and the public schools: The coproduction of education. PhiDelta Kappan, 89(8), 560-564. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217080890080

McCulloch, A. (2009). The student as co-producer: learning from public administration about the student-university relationship. Studies in Higher Education, 34(2), 171-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802562857

Mendonça, E. F. (2004). Conselho gestor como elemento de gestão democrática e de controle social de políticas educacionais. Linhas Críticas, 10(18), 117-134. https://doi.org/10.26512/lc.v10i18.3194

Meneghetti, F. K. (2011). O que é um ensaio-teórico? Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 15(2), 320-332. http://www.spell.org.br/documentos/ver/1416/o-que-e-um-ensaio-teorico-/i/pt-br

Ministério da Educação (MEC). (2014). O Plano Municipal de Educação: caderno de orientações. Secretaria de Articulação com os Sistemas de Ensino. http://pne.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/pne_pme_caderno_de_orientacoes.pdf

Miola, C., & Costa, C. (2019). Conselhos Municipais de Educação: fortalecimento da gestão democrática. Instituto Rui Barbosa. https://irbcontas.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/cartilha-conselho-municipais-de-educacao-fortalecimento.pdf

Moretto Neto, L., Salm, V. M., & Burigo, V. A. (2014). Coprodução dos serviços públicos: modelos e modos de gestão. Revista de Ciências da Administração, 16(39), 164-178. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-8077.2014v16n39p164

Nabatchi, T., Sancino, A., & Sicilia, M. (2017). Varieties of participation in public services: the who, when, and what of coproduction. Public Administration Review, 77(5), 766-776. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12765

Oliveira, V. R., & Mendonça, P. M. E. (2021). Coprodução e gestão democrática nas escolas: possibilidades analíticas de interação dos conceitos. Interface - Revista do Centro de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas, 18(2). https://ojs.ccsa.ufrn.br/index.php/interface/article/view/1109

Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073-1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

Paarlberg, L. E., & Gen, S. (2009). Exploring the Determinants of Nonprofit Coproduction of Public Service Delivery: The Case of k-12 Public Education. American Review of Public Administration, 39(4), 391-408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008320711

Peres, U., Pereira, L., Capuchinho, C., Pinheiro, Y., Machado, G., & Silva, I. (2022, outubro 27). ICMS Educacional: o que avançou nos estados e quais os riscos e incertezas para a educação? Plataforma Acadêmico Jornalística Nexo Políticas Públicas. https://pp.nexojornal.com.br/opiniao/2022/ICMS-Educacional-o-que-avan%C3%A7ou-nos-estados-e-quais-os-riscos-e-incertezas-para-a-educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o

Pestana, A., C. L., Bernardo, F. D., & Costa, R. (2020, outubro 05). Coprodução do controle: a necessidade e a possibilidade de os Tribunais de Contas irem além na abertura de suas portas. POLITEIA – Coprodução do bem público: accountability e gestão. https://politeiacoproducao.com.br/a-coproducao-do-controle-a-necessidade-e-a-possibilidade-de-os-tribunais-de-contas-irem-alem-na-abertura-de-suas-portas

Pestoff, V. (2006). Citizens as Co-producers of welfare services: preschool services in eight European countries. Public Management Review, 8(4), 503-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030601022882

Pestoff, V. (2012). Co-production and third sector social services in Europe – some crucial conceptual issues. Em V. Pestoff, T. Brandsen, B., & B. Verschuere (Eds.). New public governance, the third sector and co-production (pp. 50-83). Routledge Critical Studies in Public Management.

Radnor, Z., Osborne, S. P., Kinder, T., & Mutton, J. (2014). Operationalizing Co-Productionin Public Services Delivery: The contribution of service blueprinting. Public Management Review, 16(3), 402-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.848923

República Portuguesa. (2017). Orçamento participativo das escolas. https://opescolas.pt/regulamento

Rocha, A. C., Spaniol, E. L., Schommer, P. C., & Sousa, A. de. (2012). A coprodução do controle como bem público essencial à accountability. Anais do XXVI Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação e Pesquisa em Administração - Anpad, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil.

Rocha, A. C., Schommer, P. C., Debetir, E., & Pinheiro, D. M. (2021). Elementos estruturantes para a realização da coprodução do bem público: uma visão integrativa. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 19(3), 538–551. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395120200110

Rocha, E. (2008). A Constituição Cidadã e a institucionalização dos espaços de participação social: avanços e desafios. Em F. T. Vaz, J. S. Musse, R. F. dos Santos. (Orgs.). 20 anos da Constituição Cidadã: avaliação e desafios da seguridade social (pp. 131-148). Associação Nacional dos Auditores Fiscais da Receita Federal do Brasil.

Ronconi, L. F. de A., Debetir, E., & De Mattia, C. (2011). Conselhos Gestores de Políticas Públicas: Potenciais Espaços para a Coprodução dos Serviços Públicos. Contabilidade Gestão E Governança, 14(3). https://revistacgg.org/index.php/contabil/article/view/380

Rostirola, C. R. (2021). Dispositivos de accountability: efeitos sobre escolas públicas de ensino médio de Pernambuco. Linhas Críticas, 27. https://doi.org/10.26512/lc.v27.2021.36450

Salm, J. S., & Menegasso, M. E. (2010). Proposta de Modelos para a Coprodução a partir das Tipologias de Participação. Anais do XXXIV EnANPAD - Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Administração, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil.

Schommer, P. C., Nunes, J. T., & Moraes, R. L. (2012). Accountability, controle social e coprodução do bem público: a atuação de vinte observatórios sociais brasileiros voltados à cidadania e à educação fiscal. Publicações da Escola da AGU: Gestão Pública Democrática, 4(18), 229-258.

Schommer, P. C., Rocha, A. C., Spaniol, E. L., Dahmer, J., & Souza, A. D. de. (2015). Accountability and co-production of information and control: social observatories and their relationship with government agencies. Revista de Administração Pública, 49(6), 1375-1400. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7612115166

Silva, S. R. de A., & Nogueira, S. M. A. (2014). O Plano Municipal de Educação no contexto do desenvolvimento local e da cultura da escola. Anais do IV Congresso Ibero-Americano de Política e Administração da Educação; VII Congresso Luso Brasileiro de Política e Administração da Educação - Políticas e práticas da administração na educação Ibero-americana, Porto, Portugal. https://anpae.org.br/IBERO_AMERICANO_IV/GT1/GT1_Comunicacao/ScheilaRibeiroDeAbreuESilva_GT1_integral.pdf

Soares, G. F., & Farias, J. S. (2018). Vem educar com a gente: o incentivo de governo e escolas à coprodução da educação por familiares de alunos. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 26(101), 1347-1371. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-403620180026001299

Soares, G. F., & Farias, J. S. (2019). Com quem a escola pode contar? A Coprodução do Ensino Fundamental Público por Familiares de Estudantes. Revista de Administração Pública, 53(2), 310-330. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220170301

Suslova, S. (2016). Collective co-production in russian schools. Voprosy Obrazovaniya /Educational Studies Moscow, 4, 144-162. https://ideas.repec.org/a/nos/voprob/2016i4p144-162.html

Suslova, S. (2018). The Determinants of Collective Coproduction: The Case of Secondary Schools in Russia. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(5-6), 401-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2018.1426013

Todos pela Educação. (2018). Conselhos Municipais de Educação: o que são e como funcionam. Todos pela Educação. https://todospelaeducacao.org.br/noticias/perguntas-e-respostas-o-que-sao-e-como-funcionam-os-conselhos-municipais-de-educacao

Tribunal de Contas do Estado de Santa Catarina (TCE-SC). (2018). Portaria N. TC-0374/2018. https://www.tcesc.tc.br/sites/default/files/leis_normas/PORTARIA%20N.TC%20374-2018%20CONSOLIDADA_0.pdf

Tribunal de Contas do Estado de Santa Catarina (TCE-SC). (2022). Projeto TCE Educação. https://www.tcesc.tc.br/sites/default/files/ONLINE%20Folder_TCE_Educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o_400x200.pdf

Verschuere, B., Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2012). Co-production - The State of the Art in Research and the Future Agenda. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23, 1083-1101. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11266-012-9307-8

Flávia Antunes Souza

Flávia Antunes SouzaSanta Catarina State University, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8846-1546

Master in administration from the Fluminense Federal University (2014). Professor at the Federal Institute of Rio de Janeiro. Doctoral student in administration at the Santa Catarina State University. Member of the research group Politeia: Co-production of the Public Good – Accountability and Governance. Email: fl_antunes@yahoo.com.br

Paula Chies Schommer

Santa Catarina State University, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9919-0809

PhD in administration from the Getulio Vargas Foundation (2005). Professor of public administration at the Santa Catarina State University, leading the research group Politeia: Co-production of the Public Good – Accountability and Governance. Email: paulacs3@gmail.com

Contribution in the elaboration of the text: the authors contributed equally in the elaboration of the manuscript.

Este artigo tem como objetivo examinar teoricamente as possibilidades de atuação dos Conselhos Municipais da Educação (CMEs) na coprodução do bem público, por meio dos Planos Municipais de Educação (PMEs) e da coprodução do controle. Os CMEs são espaços propícios à coprodução do controle, visto que sua natureza formativa, funções e atribuições ensejam engajamento mútuo e contínuo entre agentes públicos e cidadãos na realização e controle de serviços educacionais. O trabalho sinaliza possíveis estudos entre os campos da educação e da gestão pública, por meio da coprodução do bem público.

Palavras-chave: Coprodução do bem público. Coprodução do controle. Conselho Municipal de Educação. Plano Municipal de Educação.

El objetivo de este artículo es examinar teóricamente las posibilidades de actuación de los Consejos Municipales de Educación (CME) en la coproducción del bien público, a través de los Planes Municipales de Educación (PME) y de la coproducción del control. Los CME son espacios propicios para la coproducción del control, una vez que su carácter formativo, funciones y atribuciones conducen al compromiso mutuo y continuo entre los agentes públicos y los ciudadanos en la realización y control de los servicios educativos. El artículo señala posibles estudios entre los campos de la educación y de la gestión pública, a través de la coproducción del bien público.

Palabras clave: Coproducción del bien público. Coproducción del control. Consejo Municipal de Educación. Plan Municipal de Educación.

Linhas Críticas | Journal edited by the Faculty of Education at the University of Brasília, Brazil e-ISSN: 1981-0431 | ISSN: 1516-4896

http://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/linhascriticas

Full reference (APA): Souza, F. A., & Schommer, P. C. (2023). Coproduction in Municipal Education Councils: possibilities for the coproduction of control. Linhas Críticas, 29, e46460. https://doi.org/10.26512/lc29202346460

Full reference (ABNT): SOUZA, F. A.; SCHOMMER, P. C. Coproduction in Municipal Education Councils: possibilities for the coproduction of control. Linhas Críticas, v. 29, e46460, 2023. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26512/lc29202346460

Alternative link: https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/linhascriticas/article/view/46460

All information and opinions in this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the opinion of the journal Linhas Críticas, its editors, or the University of Brasília.

The authors hold the copyright of this manuscript, with the first publication rights reserved to the journal Linhas Críticas, which distributes it in open access under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0