Introduction

The concept of

public policy has different definitions. Some definitions emphasize power,

actors, organizations, while others focus on the logic of State action and

intervention in specific sectors (Dye, 1984; Höfling, 2001). According to Souza

(2003), public policy is “a set of government actions that will produce

specific effects” (Souza, 2003, p. 24). Being involved in interests and

disputes, public policies are designed considering economic, social, political,

and cultural aspects of a given society, which define its contours and contexts,

as well as the arrangements with different instances.

As an analytical

framework, research has adopted the public policy cycle (Mainardes et al.,

2011) with overlapping or merging phases — Agenda, Formulation, Implementation

and Evaluation — or the research in only one of these phases (Lotta, 2014;

2015; Giusto & Ribeiro, 2019). And the least prominent one in the studies

is the implementation, both in the national and international literature since

there is a limited amount of work that investigates the elements and factors

that influence it (Dye, 1984; Oliveira, 2019; Muylaert, 2019).

This finding is

also found in studies on the public policy Sistema Mineiro de Administração

Escolar (SIMADE), a school management system implemented since 2008 by the

Minas Gerais State Department of Education (SEE/MG), and in partnership with

the Center for Policies and Education Evaluation at the Federal University of

Juiz de Fora (CAEd/UFJF)[2],

in public schools in the state of Minas Gerais. Research on SIMADE (Fonseca,

2014; Salgado, 2014; Tomaz, 2015; Balduti, 2017) presents the phases of public

policy, but the implementation is analyzed in an operational, linear way,

favoring the hierarchy of activities conducted in the system. The analysis

models of these research establish little dialogue with the debates in the

national and international literature and there is limited observation of the

performance of educational agents and the senses and meanings they attribute to

the system and its data.

Implementation is

a complex process, which involves the subjectivity of agents who, when

interpreting the texts of public policies based on their experiences, values,

and beliefs, render this stage very unpredictable (Lima, 2019). As a result,

there is in implementation a significant margin of discretion performed by

school actors, where the effective limits of their power leave them free to

make a choice between courses of action and inaction (Bonelli et al., 2019).

According to Mota et al. (2019), the exercise of discretion is inevitable and

necessary since formal rules cannot account for all concrete cases, and it is

essential that the agent exercises his power so that the organization adapts to

reality, works, and serves people. According to Lotta (2015), discretion comes

to be understood as “[…] not only as empirical evidence, but almost as a

normative ideal, insofar as the importance of autonomy for the recognition of

reality in the implementation of public policies is proven.” (Lotta, 2015, p.

28).

In the

implementation of SIMADE, discretion can be exercised by middle-level

bureaucrats (BME), who have an intermediate position between the top and bottom

of the organizational structure, which operationalize the public policies that

the higher-level ones formulate (Muylaert, 2019). In other words, they are the

“actors responsible for interacting with their subordinates and ensuring their

compliance with the implementation of rules designed by higher levels” (Fuster,

2016, p. 7). In the context of SIMADE, this actor is the principal, who, in

addition to having an essential role in organizing schoolwork, leading, and

coordinating the routine of teaching units (Drabach & Souza, 2014), puts

“the elements of the school into action organizational process (planning,

organization, evaluation) in an integrated and articulated way” (Soares &

Teixeira, 2006, p. 157).

In view of the

characterization of this agent and the delimitation of the implementation stage

of a public policy, the object of this article is to analyze the implementation

of SIMADE from the discretion of middle-level bureaucrats, the school

principals of the state public schools of Minas Gerais. In conclusion, we seek

to understand the middle-level bureaucracy in the educational context of Minas

Gerais from the profile, performance and relationships established by school

principals in accessing and using SIMADE.

Stages of SIMADE public

policy

Even with the

scarcity of studies on public policy SIMADE (Lima, 2019), research (Fonseca,

2014; Salgado, 2014; Tomaz, 2015; Balduti, 2017) allows the observation of the

interrelation between the phases and the political, historical, economic, and

educational nuances of Minas Gerais in the institution and implementation of

SIMADE.

The Agenda stage,

where “the agendas are defined according to social, political or economic

demands, on which different socioeconomic interests act” (Giusto & Ribeiro,

2019, p. 2), began between 2007 and 2010, in the second stage of the Management

Shock[3],

which the aim was to improve the quality and reduce costs of public services

through the reorganization of the institutional arrangement and management

model (Duarte et al., 2016). During this period, was adopted the

contractualization of results, having an agreement on objects and goals between

the government and the intermediary and local bodies, and the control of

results (Duarte et al., 2016).

In addition to

the contractualization of results, there was a need for real-time monitoring of

schools, so that it was possible to rationalize expenses and improve

educational results, because the Minas Gerais Public Education Assessment

System (SIMAVE[4])

repeatedly indicated student performance below expectations. Furthermore, it

was necessary to evaluate the actions and results of government interventions

more effectively. Added to this is the introduction of Information and

Communication Technologies (ICT), with initiatives from the Federal Government,

with the National Educational Technology Program (PROINFO Integrado[5]),

and from Minas Gerais, with the Escolas em Rede Project, which distributed

computers and internet to schools (Balduti, 2017).

It is in this

context that the outline of the SIMADE public policy emerges, with the aim to

promote improvements in income and performance, reduce expenses on schools, and

use the technological benefits offered by ICT, such as real-time monitoring and

data visualization in several layouts, to institute a policy of agreement on

results in which the principal is responsible for “accounting for educational

results, making him/her the main responsible for the effective achievement of

goals and objects, almost always hierarchically defined” (Duarte et al., 2016,

p. 202).

In the

Formulation stage, “which specifies the action plans, also characterized by

debates, articulation of interests and decision-making” (Giusto & Ribeiro,

2019, p. 2), SIMADE was established based on Resolution SEE no. 1,180 (Minas

Gerais, 2008), which determined the design of this public policy. The process

execution was decisive, and defined the degree of centralization/decentralization,

inspection mechanisms, guidelines and guided the implementation, in addition to

the performance of middle-level bureaucrats, making them responsible for the

insertion and updating of data from their schools.

Resolution SEE

No. 1,180 (Minas Gerais, 2008, p. 1) enacts regarding the interpretation of the

principal's role in article 6:

It is the School Principal's responsibility to

enter data into SIMADE, ensure its reliability and its periodic updating.

Sole paragraph. Changing SIMADE data can only be done by an employee

that has express permission from the School Principal.

The resolution allowed the principal to act as a user of the system,

i.e., the street-level bureaucrat (those who act directly in contact with users

of public services, affecting performance, quality and access to goods and

services promoted by the government), or as a BME. As found in the research by

Fonseca (2014), Tomaz (2015) and Balduti (2017), in the school context, few

principals (about 20%) claim to exercise this dual role, since because of the

daily tasks and the complexity of the role of principal, the system user is the

school secretary and the other members of the school secretary staff.

Therefore, these professionals are the street-level bureaucrats in the context

of SIMADE.

The next stage,

Implementation, is characterized as “the moment when the guidelines are

effectively put into practice with the target audience” (Giusto & Ribeiro,

2019, p. 2). Traditionally, studies on the implementation of public policies

tended to focus on the performance of activities established from the top down,

as pointed out by Lotta (2015) and Oliveira (2019), in an analytical

perspective referred to as policy

centered. The implementation object was to achieve goals previously set in

the policy formulation process, being considered as prescriptive and

hierarchical, as in the top-down

model, in which actors were subjected to decision makers and there was an

automatic translation between decision and action. These could also be

descriptive and flexible, as in the bottom-up

model, which emerged in the following decades, and values the observation of

the policies effectiveness and evaluation, as well as the factors that cause

failures in the implementation process. When analyzing the implementation, in

both cases there was a gap between the formulation and the execution,

separating administrators and executors, making the existence of different

forms of implementation to be considered having different motivations and degrees

of autonomy among the implementers (Muylaert, 2019; Oliveira, 2019).

It breaks,

therefore, with the linear perspective in which public policies are implemented

as elaborated and described in the formulation, since in the implementation

there is a process of re-readings, reinterpretations, changes of meanings and

translations by the actors when placing the public policy in practice. This

public policy perspective values negotiation and action and is considered a

second generation of implementation studies.

Recent studies

(Lotta, 2015; Oliveira, 2019; Muylaert, 2019), summarizing the contributions of

previous analysis models, understand the implementation process as central and

continuous, in which one of the basic elements of analysis is the discretion of

the implementing agents and of middle-level bureaucrats. In this sense,

discretion “becomes focused on an action of viewing the implementation as a set

of tensions, interactions, and strategies which involve decision-making”

(Oliveira, 2019, p. 3).

The implementation of SIMADE, based on the top-down model, began in

January 2008, with the participation of 56 instructors and 9 analysts[6]

subordinated to CAEd/UFJF, which in partnership with SEE/MG coordinated and

monitored the entire implementation in the 3,920 state schools[7].

From March 2010, having the system already with its online version [8],

From March 2010, having the system already with its online version, the

implementation was conducted by technicians from the 43[9] Regional

Education Superintendencies (SREs), although support [10] for

system users was still conducted by the CAEd (Remote Learning Support Center).

In October 2016, SIMADE started to be managed only by SEE/MG, although the CAEd

was still responsible for supporting the users of the system until December of

the same year. In January 2017, SIMADE became the exclusive responsibility of

SEE/MG and service to users began to be conducted by the SREs teams (Balduti,

2017).

The evaluation

stage, “which uses some measurement instrument to verify the results obtained,

comparing them with the formulated specifications and the planned objects”

(Giusto & Ribeiro, 2019, p. 2), has been conducted through mixed (Fonseca,

2014; Tomaz, 2015; Balduti, 2017) or qualitative (Salgado, 2014) research. Such

researches indicate that there is little detail regarding the policy

formulation, leaving only what is prescribed by Resolution 1,180 (Minas Gerais,

2008), and that the implementation does not present a dialogue with the demands

of the schools and professionals heading the management since it used the top-down model. Furthermore, the

evaluation focuses on the effects of the system, without associating them with

a stage analysis of the public policy cycle and implementing bureaucrats at

distinct levels involved in the development, access, and use of the system.

Therefore, there is a need to introduce the role of implementing bureaucrats

and their discretion in SIMADE public policy into the analytical agenda.

Mid-Level Bureaucrats:

School Principals in the State of Minas Gerais

In recent

decades, the public policy literature has made important advances in

understanding the role of bureaucrats in the policymaking process. However, the

studies focused especially on high-level and street-level bureaucrats, in which

these are the highlights of the field, disregarding the relevance of

middle-level bureaucrats in different instances of the government and of the

public and private management (Cavalcante et al., 2017; Mota et al., 2019).

Since they occupy

an intermediate position, middle-level bureaucrats are in the conceptual

“limbo” between the top-down and bottom-up models, as they are situated

between the top and the bottom (Oliveira & Abrucio, 2018), due to the

variety and heterogeneity of actors in different sector and institutional

contexts, in addition to the specifics of the positions (Pires, 2015).

Middle-level bureaucrats are difficult to understand because they are defined

in relation to the position occupied in each policy or in each government

structure, to the detriment of specific, proper, and equal characteristics in

all public agencies and policies (Lotta et al., 2014).

However, Lotta et

al. (2014) and Oliveira (2019), note in an extensive review of national and

international publications that the literature has made some progress. Mention

can be made, among these, to the perception of similarities and differences

between middle-level bureaucrats, since each context involves specific

realities that determine who they are and what they do.

The theoretical

framework on implementing bureaucrats in studies on implementation coming from

Political Science and recently appropriated in the field of education (Lotta,

2014; Mota et al., 2019) comprises the school principal — an employee linked to

a federal education unit, state or municipal, occupying a commissioned position

— such as BME. As much as the school principal has daily contact with the

students and/or their family/guardians (who are the beneficiaries of the

educational service) through their tasks, the set of their attributions are

that of professionals who work at the intermediate level of the bureaucratic

hierarchy, i.e., the principal's tasks make him a link between the upper level

and the street level. Thus, based on the literature on implementing agents

(Lotta et al., 2014; Cavalcante & Lotta, 2015; Muylaert, 2019), the school

principal is considered a BME.

According to

Lotta et al. (2014, p. 465), middle-level bureaucrats are “actors who play a

management role and intermediate direction (as managers, principals,

coordinators, or supervisors) in public and private bureaucracies” in the

processes of public policy implementation. BMEs act to transform political

strategies into operational decisions and, to this end, establish horizontal

(with colleagues) and vertical connections (with subordinates and superiors),

also helping to understand how public administration works (Cavalcante et al.,

2017).

In the SIMADE

public policy, middle-level bureaucrats are the school principals responsible

for the maintenance and periodic updating of the system, complying with

SEE/MG's designs, as well as coordinating the performance of school secretaries

in the system use. In Minas Gerais, the position of school principal is held by

public employees — contracted or permanent — who have participated in an

Occupational Certification process[11]. This

process aims to select education professionals who have technical knowledge,

measured through tests, and who are also chosen by the school community via

election to assume the position of principal of state schools (Fonseca, 2014;

Tomaz, 2015). In this way, when invested in a public office, the principal

exercises an administrative role that links him to the authority that appointed

him/her in terms of the school he/she directs and represents, creating a link

between the State and the school community (Muylaert, 2019). Thus, the

principal connects to the upper echelon, SEE/MG, and to the school and to all

the actors that compose it.

In the daily life

of schools, principals as BME play a dual role: technical-managerial and

technical-political. In a technical-managerial role, “the actions concern how

these bureaucrats translate strategic determinations into everyday actions in

organizations, building standards of procedures and managing the services,

therefore, the implementing bureaucrats” (Lotta et al., 2014, p. 472). The

second role, technical-political, concerns “how these actors build negotiations

and bargains related to the processes in which they are involved and their

relationship with the highest level” (Lotta et al., 2014, p. 473). However,

this role depends directly on the position of the BME in the chain of actors,

between formulation and implementation.

Therefore, the

actions of agents and the relationships they establish make it possible to

understand the processes of implementation of public policies. According to

Lotta et al. (2014), the absence in the literature on middle-level bureaucrats

deserves greater attention since it offers important analytical and

interpretive gains, in addition to understanding the effects on implementation

and its network of interactions and processes.

Methodological paths

This article is

the result of research conducted in the Doctor’s Degree in Education of the

Postgraduate Program at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro

(PUC-Rio). Having as its object of study SIMADE and the discretion of school

principals, this research adopted a mixed approach, combining collection

techniques and qualitative and quantitative analysis.

To this end, in

2019, an online questionnaire was applied to 3,444 principals of schools that

offer regular education and serve 2,137,891 students from the state public

school of Minas Gerais. The document consisted of 38 questions that dealt with

the respondent's profile, access, and use of SIMADE. As this is a research

conducted with human beings, both SEE/MG and each school principal virtually

signed the Free and Informed Consent Term, as requested by the PUC-Rio Ethics

Committee, to which this work was submitted and approved. In order to preserve

the anonymity of the respondents, fictitious names were assigned to each

response from the principals.

The 586

questionnaires that were answered by the school principals were analyzed using

the SPSS software (version 18), which made it possible to trace the profile of

the respondents and the characteristics of access and use of SIMADE, as well as

to identify the discretion exercised by middle-level bureaucrats.

Then, the open

question “What is your responsibility in relation to SIMADE?” was selected,

which allowed a space for less guided expression of the respondent on the

subject to understand the principal's discretion. The 586 responses were

compiled from content analysis which, according to Carlomagno and Rocha (2016,

p. 175), “is intended to classify and categorize any type of content, reducing

its characteristics to key elements, so that they are comparable to a number of

other elements”. For the treatment of data, the categorical analysis technique

was based on differentiating the nuclei of meaning that constitute the

communication to later regroup them in categories. Thus, two categories are

founded: administrative, composed of 525 schools; and pedagogical, composed of

27 schools.

BME Characteristics

In the 586

schools, 93.3% of respondents hold the role of school principal and only 6.7%

hold the role of deputy principal, predominantly women (72.1%) who ascended to

the role through a selection process and election (94.5%). Regarding color,

there is a predominance of white (50.5%), followed by brown (41.1%), a result

similar to that observed by Soares and Teixeira (2006). The average age is 48

years old, although the predominant age groups are from 41 to 50 years old

(39.9%) and from 51 to 60 years old (38.6%), like the results from studies by

Tomaz (2015) and Balduti (2017).

Most of the

principals (96.7%) have already worked as regents in basic education, with an

average of 15 years, while as a school principal and performing the management

of the current school (where they participate in the survey) the average is

less of 2 years. As each term lasts four years, these principals and deputy

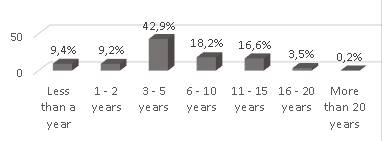

principals are in their first term, as illustrated in the following chart:

Graph 1

Period as a principal in this school[12]

Source: Lima

(2019, p. 85).

The graph also

indicates that there is significant shift in the position, as only 38.5% of

principals have been principals for more than 6 years. This result is

associated with the legislation of the state of Minas Gerais, which until 2018

allowed only one consecutive re-election to the position of principal.

According to Lima (2019), ascension to the position by selection process and

election allows for a more consistent choice when selecting the best

candidates, using technical competence and the appreciation of the school

community.

Regarding

schooling, managers are mostly graduated in Pedagogy and Mathematics,

respectively 8% and 6%, Biology, Literature and History, around 5% each[13].

Among the principals, as already observed in numerous surveys (Tomaz, 2015;

Balduti, 2017), those with postgraduate degrees predominate, around 70%, and 6%

have completed the School Management course, 5.4% the Supervision course, 4%

the mathematics course, 3.7% the Psychopedagogy course and 3.1% the School

Inspection course.

About 60% of the

principals consider that they have a good working relationship with the school

secretaries, which is fundamental for the functioning of the school unit in the

administrative scope and for the use of SIMADE. Lima (2019) notes that the

perception of the environment is significantly associated with a strong

alignment of school actors in relation to the mission and vision they share

about the teaching unit.

Among the 586

principals, 65% claim to dedicate between 1 to 5 hours a week to external

relations, which include meetings and/or contact with the Regional Education

Superintendence (SRE), which passes on the SEE/MG guidelines. In other words,

it is easier to be complacent with the rules and norms coming from high-level

bureaucrats (Fuster, 2016), sometimes in an innovative and sometimes

conservative way (Oliveira, 2019), i.e., with a flexible margin of discretion.

These results

also highlight the relational dimension of the work of the BME, which, as they

are at the intermediate level with horizontal and vertical work relationships,

have information that regulates their relationships, in addition to maintaining

the frequent flow of school monitoring (Cavalcante et al., 2017).

They build (or produce) their position through the management of these

information flows — they demand with more or less intensity, decide what “goes

up” and what “does not go up”, […], decide how to balance the tensions between

the various actors with whom they interact, they manage the necessary measures

and referrals. (Pires, 2015, p. 217)

Thus, it is

middle-level bureaucrats who define the functioning of the school, articulating

horizontal and vertical relationships, building consensus among actors to

achieve their goals. Therefore, they are an intermediary agent between the

upper level and the street-level bureaucrats.

The role of school

principals in the implementation of SIMADE

According to Mota

et al. (2019), the implementation of public policies should be considered to

observe the performance of the actors, as well as the potential for adjustments

that this stage represents in relation to the formulation of the policy. Regarding

the use of SIMADE, specifically related to the frequency of access, only 7.84%

of the principals said they do not use the system and approximately 20% report

that the use occurs through the secretariat employees, i.e., they do not access

it directly. About 70% of principals frequently access the system.

The formulation of the SIMADE public policy leaves a space for decision

for the principal to act as a user or as an observer of the information entry,

since it does not explain what is expected from SIMADE users regarding the

system and the data access and use, broadening the exercise of discretion. The

difference between observers and users is the attendance to a training course

on SIMADE, which can foster understanding on the system and its importance for

school management. Furthermore, the observer principals work in schools that

offer initial grades (82) or complete elementary education (93); while the user

principals' schools serve elementary school (355) or high school (43). Although

the frequency of use of the system depends on the way principals interpret and

understand their action in the school, which is difficult to capture by the

survey, these responses seem to indicate that the training associated with the

steps taken can influence the use of the system.

Middle-level

bureaucrats manage the gap in the rule and use different practices with

adaptations and translations of regulations to achieve their results (Lotta,

2014). Therefore, there is a recontextualization of the original discourse to a

context in which it is modified, condensed and re-elaborated (Oliveira, 2019)

by about 30% of the principals, who understand that access to SIMADE is not

their task.

This result is

consistent with the findings of Cavalcante and Lotta (2015) and Cavalcante et al.

(2017) that the environment in which the BME operates offers different forms of

action and discretion in relation to public policy. The two forms of access —

through the secretary and the school principal himself — respectively refer to:

(i) the proximity of the principals to the street-level bureaucrats (in this

case the school secretaries), since they are the users of SIMADE and the actors

who maintain the dialogue with the beneficiaries of the policy (the students

and/or parents or guardians) and are responsible for providing the principal

with all the data necessary for the management of the school; (ii) when using

the system and possibly understanding its data, the principal comes closer to

the high-level bureaucrats because he/she is more capable to understand the

political decisions emanated by the bureaucrats high-level, in addition to

knowing and monitoring the data of his own school. It is worth mentioning, as

observed by Cavalcante et al. (2017), that the interaction between internal

actors (principals and school secretaries) and external actors (SEE/MG and

SRE), the technical nature of decisions and the very degree of discretion, can

bring about different outlines to access to the system and to the public

administration.

This result is

consistent with the answers given by the principals about their responsibility

in relation to the use of SIMADE[14].

Some answers were selected to illustrate the principals' perception:

(i) answer group

1 – to keep updated and correct data for a true and concrete analysis

(Margarida, 44, principal); to designate and supervise the responsible

secretary and carry out some more specific actions when necessary (Jasmim, 40,

principal); to monitor the entry of reliable data and its constant updating

(João, 37, principal); to supervise, the service is performed by the

secretariat (José, 47, principal); to enforce all actions inherent to it,

inspecting access by the secretary and punctuality in providing data (Rosa, 33,

principal); to supervise, the service is performed by the secretariat.

(Amarílis, 42, principal)

(ii) answer group

2 – to weekly open together with the pedagogical staff to check attendance,

evasion, pedagogical performance (Azaleia, 51, principal); to monitor evasion,

dropout and student performance rates and develop plans of goals and actions

for intervention with the support of the school supervisor (Camélia, 45,

principal); to verify, together with the pedagogical team, the strategies that

should be elaborated for better student performance and to reduce school

evasion. (Paulo, 49, principal)

In the first

group, composed of 525 principals, a supervisory role is assumed, supervising

the execution of tasks, aiming only at the fulfillment of the activities that

must be conducted in SIMADE. As noted by Muylaert (2019), the principal plays a

well-defined role in most public policies, which is the task of coordination.

In this perspective, as highlighted by Salgado (2014) and Tomaz (2015), there

is a predominance of the technical use of the system, i.e., for the purpose of

complying with Resolution 1,180 (Minas Gerais, 2008), which aims to control the

school unit, in addition to contributing to the implementation of school

services in a standardized way. In particular, this type of perception of

responsibility proposes a new form of regulation — centered on the definition

and a priori control of results, whose aim is to ensure coherence, balance, and

identical reproduction of the use of SIMADE by all schools, through practices

that allow the control and recording of what happens in the teaching units.

In the second

group, formed by 24 managers, the use of the system focuses on the information

that can be extracted and can contribute to the improvement of student learning

and to the quality of education. The student seems to be the focus and the data

extracted can facilitate monitoring, enabling monitoring of student and school

performance, which can ensure data that allow diagnosis and propose strategies

for improving the quality of education.

In this context,

the principal, through the system data, can promote the necessary conditions

for the implementation of improvements in the school, particularly those of a

pedagogical nature. It seems to us that the principals of group 2, unlike those

of group 1, produce a new rule that is not limited to the systematic and full

compliance with Resolution 1,180 (Minas Gerais, 2008) when using the system to

monitor and make decisions within schools.

Although these

two categories are already widely discussed and verified in the literature that

investigates the daily life of school management (Werle & Audino, 2015;

Leal & Novaes, 2018) and how these are identified as focused on

administrative matters — accountability, budget collection, organization of

timetables and financial — and/or pedagogical — control — curriculum,

assessment, teaching methodology and performance analysis — the study in

question indicates that there is a lack of clarity in the object of formulating

the policy, which may be causing two different forms of implementation and

consequently two uses of the system from the discretion of school principals.

On the one hand,

the aim is to achieve greater compliance with educational standards; and, on

the other hand, the search for better performance and better student

performance, which appears to indicate that there is appreciation of a

pedagogical management of the school based on data provided by the system.

“Although there are rules and norms that shape some standards of action, these

bureaucrats still have the autonomy to decide how to apply them and insert them

into implementation practices” (Lotta, 2015, p. 46). In this way, SIMADE is

understood only as a standardization and control instrument, to the detriment

of being a pedagogical tool that influences educational efficiency and school

management.

This result

corroborates the statement by Lotta et al. (2014), because the diversity of the

implementation context can cause the same regulation to produce entirely

different results in different realities, even though they are predominantly

schools that serve the final years of elementary and high school (60%). That

is, the school context can be affected by the type of system use, although the

actions, values, and references of the principals also influence and transform

the way the policy was conceived.

In addition, both

access and perception of the principal's responsibility in relation to the use

of SIMADE are related to the ability to influence decisions, as pointed out by

Cavalcante et al. (2017). These variables materialize in the SIMADE public

policy, in the verification of schools in which the principals claim that the

use of SIMADE is compatible with the way secretaries perform it, i.e., in 525

teaching units, principals and secretaries use the system in an administrative

way. According to Lima (2019), due to the duties of the secretary's position

focused on the bookkeeping, registration and organization of information, these

professionals are not dedicated to the pedagogical dimension and, therefore, do

not envision SIMADE as pedagogical. It is hypothesized that, as 61.5% of

principals are in their first term or at the beginning of their second, they

may be using the system according to the vision of the school secretaries,

which is in line with the purposes of SEE/MG materialized in Resolution 1,180

(Minas General, 2008).

In these cases,

there seems to be considerable alignment between principals and secretaries,

who share perceptions about the system in a productive collaborative

relationship that can have a positive impact on the school atmosphere, as

pointed out by 60% of principals, and on the use of the system and its data.

After all, the fact that the alignments between principals and secretaries are

aimed at the administrative aspect indicates that the regulation proposed by

the State since the Management Shock policy (Duarte et al., 2016), as well as

the accountability of principals for student results (Drabach & Souza,

2014), is still very present.

Although the

pedagogical use of SIMADE may be a consequence of other factors that have a

much more significant weight in education, such as, for example, the social

origin of students and the didactic-pedagogical actions of the teacher (Soares

& Teixeira, 2006), the following hypothesis is recorded here for future

studies: the 24 schools can aim to ensure educational quality, via increased

student performance and intra-school equity, adopting actions based on evidence

provided by SIMADE, since “the same set of school practices can act,

concomitantly increasing the average performance of schools and promoting

equity among students” (Lima, 2019).

The result of the

24 schools reflects, in opposition to what was observed by Bonelli et al.

(2019) in the application of Agency Theory[15], in a

synchronicity between the use of the system by principals and secretaries that

can generate informational strategies, articulating certain administrative

and/or pedagogical information from the perspective of each actor that allow

raising educational evidence about the teaching unit and a meaningful use of

system data for the school context. As noted by Giusto and Ribeiro (2019), when

analyzing street-level bureaucrats, there is, as for BME, “a freedom of action,

especially when faced with ambiguous and contradictory rules” (Giusto &

Ribeiro, 2019, p. 4), which allows secretaries to make their own interpretation

of public policy based on their previous experience, something that can be

considered when providing information to the BME. It seems to us that in these

schools, even with divergent views on the system, the performance of the school

secretaries and the BME is articulated and complemented in favor of the

students' results.

Therefore, school

principals are responsible for coordinating the implementation of the SIMADE public

policy and, at times, articulate and build consensus among the different actors

involved, as in schools where the use of the system is administrative or

pedagogical. Due to their intermediate position in the organizational

structure, principals make decisions to be put into action, but they also

exercise discretion, which may aim to improve quality and equity in public

schools in the state of Minas Gerais.

Conclusion and final

remarks

The School

Administration System of Minas Gerais (SIMADE) allows middle-level bureaucrats

to have a significant margin of discretion in accessing and using the system,

which reverberates in new directions and meanings for public policy and

consequently for its implementation. In addition, the formulation of this

policy structured in a prescriptive and hierarchical manner is far from

implementation, since the former did not explain much about access and mainly

about the use of the system, allowing a great margin of discretion for the

principals and even the no access to the system. Both in terms of access and

usage, the BME sometimes approaches the top level, having a pedagogical use

that allows it to monitor the performance of students and the school; sometimes

he/she approaches street-level bureaucrats, being a supervisor of the actions

developed in the system.

Furthermore, in

the form of implementation aimed at the administrative use of SIMADE, based on

Resolution 1180/2008 (Minas Gerais, 2008), the BMEs are in line with the

statement provided by the highest level in a managerial perspective, which

values control, standardization, efficiency in the public service. On the other

hand, there is the production of a new rule in the implementation focused on a

pedagogical perspective that is not limited to the systematic and full

compliance with the aforementioned resolution but uses SIMADE data to monitor

and make decisions within schools. Since it was instituted under the Management

Shock Policy, SIMADE contributes to a larger public policy, which is

educational, being a means to achieve certain educational purposes.

The limits of

this study, which result from the methodological approach, circumscribe the

starting points for future qualitative researches, with the possibility to

investigate the use of administrative and pedagogical data from practices and

profiles of the principal; organizational complexity of the school (secretaries

and their interactions with management); stages and student profiles

(socioeconomic level, income, etc.). Such studies can reveal technical, political,

and managerial aspects established and carried out by high-level bureaucrats,

in addition to promoting evidence on the need to train principals to use

SIMADE.

References

Balduti, C. F. (2017).

Possibilidades de aperfeiçoamento do Sistema Mineiro de Administração

Escolar (SIMADE). [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal de Juiz de

Fora]. Repositório Institucional da UFJF. http://mestrado.caedufjf.net/possibilidades-de-aperfeicoamento-do-sistema-mineiro-de-administracao-escolar-simade

Bonelli, F.,

Fernandes, A. S. A., Coêlho, D. B., & Palmeira, J. da S. (2019). A atuação

dos burocratas de nível de rua na implementação de políticas públicas no

Brasil: uma proposta de análise expandida. Cadernos

EBAPE, 17(1), 800-816. http://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395177561.

Carlomagno, M. C.,

& Rocha, L. C. da. (2016). Como criar e classificar categorias para fazer

análise de conteúdo: uma questão metodológica. Revista Eletrônica de Ciência

Política, 7(1), 173-188. http://doi.org/10.5380/recp.v7i1

Cavalcante, P. L.,

Lotta, G. S., & Yamada, E. M. K. (2017). O desempenho dos burocratas de

médio escalão: determinantes do relacionamento e das suas atividades. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 16(1),

14-34. http://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395167309

Cavalcante, P., &

Lotta, G. (2015). Burocracia de Médio Escalão: perfil, trajetória e atuação.

ENAP. https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/2063

Drabach, N. P., &

Souza, A. R. de. (2014). Leituras sobre a gestão democrática e o

“gerencialismo” na/da educação no Brasil. Revista

Pedagógica, 16(33), 221-248. https://doi.org/10.22196/rp.v16i33.2851

Duarte, A., Augusto,

M. H., & Jorge, T. (2016). Gestão escolar e o trabalho dos diretores em

Minas Gerais. Poiésis, 10(17), 199-214. http://doi.org/10.19177/prppge.v10e172016199-214

Dye, T. R.

(1984). Understanding Public Policy. PrenticeHall.

Fonseca, J. F. (2014).

Gestão Escolar em Rede: estudo de caso de proposta de melhorias do Sistema

Mineiro de Administração Escolar na Superintendência Regional de Ensino de Ouro

Preto. [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora].

Repositório Institucional da UFJF. http://mestrado.caedufjf.net/gestao-escolar-em-rede-estudo-de-caso-e-proposta-de-melhorias-do-sistema-mineiro-de-administracao-escolar-na-superintendencia-regional-de-ensino-de-ouro-preto

Fuster, D. A. (2016).

Burocracia e políticas públicas: uma análise da distribuição e ocupação dos

cargos e funções em comissão da prefeitura de São Paulo. Em IX Congresso

CONSAD de Gestão Pública, Brasília, DF, Brasil. http://consad.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/BC-Gest%C3%A3o-de-Pessoas-07.pdf

Giusto, S. M. N. Di.,

& Ribeiro, V. M. (2019). Implementação de Políticas Públicas: conceito e

principais fatores intervenientes. Revista de Estudios

Teóricos y Epistemológicos en Política Educativa, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.5212/retepe.v.4.007

Höfling, E. de M.

(2001). Estado e políticas (públicas) sociais. Cadernos Cedes, 23(55),

30-41. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-32622001000300003

Leal, I. O. J., &

Novaes, I. L. (2018). O diretor de escola pública municipal frente às

atribuições da gestão administrativa. Regae: Revista de Gestão e Avaliação

Educacional, 7(14), 63-77. https://doi.org/10.5902/2318133830020

Lima, C. da C. de. (2019).

Uso dos dados do Sistema Mineiro de Administração Escolar (SIMADE) pelos

gestores das escolas públicas da Rede Estadual. [Tese de doutorado,

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro]. Repositório Institucional

da PUC-Rio. https://www.maxwell.vrac.puc-rio.br/colecao.php?strSecao=resultado&nrSeq=50967@1#

Lotta, G. S. (2014).

Agentes de implementação: uma forma de análise de políticas públicas. Cadernos

Gestão Pública e Cidadania, 19(65), 186-206. http://doi.org/10.12660/cgpc.v19n65.10870

Lotta, G. S. (2015). Burocracia

e implementação de políticas de saúde: os agentes comunitários na estratégia de

saúde da família. Fiocruz.

Lotta, G. S., Pires,

R. R. C., & Oliveira, V. E. O. (2014). Burocratas de médio escalão: novos

olhares sobre velhos atores da produção de políticas públicas. Revista do

Serviço Público, 65(4), 463-492. https://doi.org/10.21874/rsp.v65i4.562

Mainardes, J.,

Ferreira, M. dos S., & Tello, C. (2011). Análise de políticas: fundamentos

e principais debates teórico-metodológicos. Em S. Balls, & J. Mainardes

(Orgs.). Políticas Educacionais: questões e dilemas (pp. 143-174).

Cortez.

Minas Gerais. (2008). Resolução

SEE n.º 1.180 de 28 agosto de 2008 (Dispõe sobre as diretrizes e

orientações para implantação, manutenção e atualização do Sistema Mineiro de

Administração Escolar (SIMADE)). Diário Oficial do Estado de Minas Gerais. https://www2.educacao.mg.gov.br/images/documentos/1180_r.pdf

Mota, M. O., Biar, L.

de A., & Ramos, M. E. (2019). A implementação do Programa de Alfabetização

na Idade Certa no Estado do Ceará. Revista de Estudios

Teóricos y Epistemológicos en Política Educativa, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.5212/retepe.v.4.008

Muylaert, N. da C.

(2019). Diretores escolares: burocratas de nível de rua ou médio escalão? Revista Contemporânea de Educação, 14(31),

84-103. https://doi.org/10.20500/rce.v14i31.25954

Oliveira, A. C. P. de.

(2019). Implementação das Políticas Educacionais: tendências das pesquisas

publicadas (2007-2017). Revista de

Estudios Teóricos y Epistemológicos en Política Educativa, 4(1).

https://doi.org/10.5212/retepe.v.4.009

Oliveira, V. E., &

Abrucio, F.L. (2018). Burocracia de médio escalão e diretores de escola: um

novo olhar sobre o conceito. Em R. Pires, G. S. Lotta & V. E. Oliveira

(Orgs.). Burocracia e políticas públicas no Brasil: interseções analíticas (pp.

207-225). ENAP. http://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/3247

Pires, R. (2015). Por

Dentro do PAC: arranjos, dinâmicas e instrumentos na perspectiva dos seus

operadores. Em P. Cavalcante & G. H. Lotta (Orgs.). Burocracia de Médio

Escalão: perfil, trajetória e atuação (pp. 177-222). ENAP. http://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/2063

Salgado, A. F. C.

(2014). Análise da gestão da informação no Sistema Mineiro de Administração

Escolar (SIMADE) pelas superintendências regionais de ensino. [Dissertação

de mestrado, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora]. Repositório Institucional

da UFJF. http://mestrado.caedufjf.net/analise-da-gestao-da-informacao-no-sistema-mineiro-de-administracao-escolar-simade-pelas-superintendencias-regionais-de-ensino

Soares, T. M., &

Teixeira, L. H. G. (2006). Efeito do Perfil do Diretor na Gestão Escolar sobre

a proficiência do aluno. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, 17(34),

155-186. https://doi.org/10.18222/eae173420062121

Souza, C. (2003).

Estado do campo da pesquisa em políticas públicas no Brasil. Revista

Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 18(51), 15-20. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-69092003000100003

Tomaz, P. A. (2015). Possibilidades

de usos das informações do Sistema Mineiro de Administração Escolar na gestão

das escolas. [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Federal de Juiz de

Fora]. Repositório Institucional da UFJF. http://mestrado.caedufjf.net/possibilidades-de-uso-das-informacoes-do-sistema-mineiro-de-administracao-escolar-na-gestao-das-escolas

Werle, F. O.

C., & Audino, J. F. (2015). Desafios na gestão escolar. RBPAE, 31(1),

125-144. https://doi.org/10.21573/vol31n12015.58921