Introduction

One of the goals of education is for learning to

persist over time. However, it is common for students to complain about not

being able to remember the content they have studied. One of the reasons is

that they do not prefer to use the best strategies to learn (Karpicke et al.,

2009; Dunlosky et al., 2013; Karpicke et

al., 2014; Ekuni et al., 2020). Given that, several research in the field of

Cognitive Psychology, both in laboratories and educational settings, point to

strategies that promote long-lasting learning, such as retrieval practice

(Dunlosky et al., 2013).

Retrieval practice is a learning

strategy that aims to try to remember content previously seen, either through

tests (multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blanks, short-answer, etc.) or through

exercises that stimulate retrieval (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006a). During the

encoding of information (which occurs, for example, when attending a class,

reading a text, etc.), information is put in our head. When trying to remember,

however, we search for this information, trying to put it out of our

head (Agarwal & Bain, 2019). In this attempt, our brain elaborates and

relates available routes (pathways) to identify information we have previously

accessed (Bjork, 1975) and activates semantically related content (Carpenter,

2011). This means that when we find the content we are looking for in our mind,

information is reconsolidated, its access is facilitated, and the memory trace

is strengthened, making it more lasting (Van den Broek et al., 2016).

Historically, experiments testing the effects of

retrieval practice date back more than a century. The papers reviewed converge

on an experiment conducted by Abbott (1909), which is indicated as the initial

milestone of studies in this field (Yang et al., 2021). Abbott's finding, later

replicated by numerous researchers, is that testing learned knowledge alters

its retention in memory (Abbott, 1909; Roediger & Karpicke, 2011). The

heyday of research on remembering practice, however, would only come up in the

1960s and 1970s from the publication of other relevant papers regarding topics

pertinent to the Cognitive Psychology of Memory (Roediger & Karpicke,

2011). Despite a century of research in the field, Agarwal and Bain (2019) state

that pedagogical “fads" are shown in teacher education courses and end up

leaving evidence-based teaching strategies out of it. Perhaps this explains why

retrieval practice is not widely seen as a teaching strategy in everyday school

life.

Among its benefits, retrieval practice improves

metacognition (McDermott, 2021), decreases anxiety on later tests (Agarwal et

al., 2014), provides feedback on what one knows and what one does not

know, thereby making room for future studies (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b). Another advantage is that it involves no

additional financial investment (Roediger & Pyc, 2012) and can be adapted

to a variety of educational materials and teaching methods (Agarwal et al.,

2018).

As stated, one of the ways to practice retrieve can

be through tests, for when a student sees a certain question, he must try to

extract the answer from his head. However, in educational practice, tests are

usually used as a form of assessment (i.e., school exams), not as a learning

strategy (Yang et al., 2021). Implementing retrieval practice in education is

important in the sense of promoting long- lasting learning and encouraging

students to engage in their own cognitive processes through effective study

strategies (Ekuni et al., 2020).

Education needs scientifically proven methods that

enable concrete effects in the school environment (Slavin, 2020). Therefore,

the use of more effective learning strategies can benefit students. In view of

the above, the present study aimed to conduct a narrative review, a style of

review that does not require following a systematic protocol, so that it is not

necessary to inform the search methodology of the references (Rother, 2007).

This review can be done by the author himself, without having to explain the

criteria for the search and selection of sources (Collins & Fauser, 2005).

However, one should ensure academic eloquence from the author's critical

analysis of the published literature (Rother, 2007). Likewise, care must be

taken so that the sources selected are based on scientific studies that have

proven to be effective (Slavin, 2020). Following these guidelines, it is

possible to establish a relationship between productions on previously defined

topics, consolidate concepts and provide practical guidance (Elias et al., 2012).

Thus, in narrative reviews, the bibliographic productions are analyzed in such

a way that they result in a state-of-the-art on the topic in which the

researcher intends to delve (Elias et al., 2012).

To analyze the use of different test formats as learning

strategies, as explained above, we used the narrative review method. As

inclusion criteria we used papers that focused on tests as a learning strategy,

and not as an assessment tool. In fact, the purpose of using these strategies

is not to evaluate the student, but to encourage him to try to remember the

content learned. In this sense, the literature knows this phenomenon as testing-effect, test-enhanced learning,

retrieval-based learning, retrieval

practice, terms we used in the searches we did in databases through a

non-systematic way. Finally, we provide recommendations and tips to teachers

and students to implement retrieval practice in the teaching and learning

process.

True or false

True or false (T/F) questions

are answer selection questions, meaning that the respondent must recognize the

answer to be selected by deciding whether a statement is false or true

(Santrock, 2009). For example: Castle Geyser is the oldest geyser in

Yellowstone Park: (T) / (F).

From the point of

view of their advantages, questions of this type are commonly used in the

classroom and are pedagogically practical to administer because they are

objective in measuring results (score is based on right answers) and require

less prep time (Uner et al., 2022). Furthermore, this type of test allows a

large number of questions to be covered in a common testing period (Santrock,

2009). If there are situations where it is difficult to create several lures,

i.e., plausible alternatives to multiple choice questions, this type of test is

also useful (Uner et al., 2022).

T/F tests result in

benefits also for children. For example, research involving students (eleven years-old on average) in a classroom setting found

positive effects on cognitive (correctness of answers) and metacognitive (level

of confidence in answers) performance from experiments involving T/F questions

on History, Politics, and Geography content (Barenberg & Dutke, 2019). As

indicated by experiments conducted with nearly five hundred university participants employing

Biology content in virtual learning environments, T/F questions can also

be beneficial in e-learning or b-learning scenarios, especially when

feedback is present (Enders et al., 2021).

Conversely, the

pedagogical effectiveness of T/F tests may not be as powerful compared to other

test formats, as indicated by experiments conducted with undergraduates in a

laboratory setting using texts (Brabec et al., 2021). Thus, among the possible disadvantages of applying this type of test are blind

guesses (i.e., attempts to get it right at random) and negative suggestions. In

the latter case, by reading the lure (false information) the student may learn

it and recognize it in other tests in the future,

taking it for granted (Uner et al., 2022). In this vein, in experiments

conducted with undergraduates, Brabec et al. (2021) found evidence of negative

suggestion when participants had to choose the true alternative compared to not

being tested with T/F questions (control condition). According to the authors,

this negative effect may be lessened with the presence of feedback (Brabec

et al., 2021).

To try to minimize this

catch, as well as to avoid blind guesses, an experiment conducted with

Psychology students, demanded participants to provide a justification for each

selected answer (Schaap et al., 2014). As can be seen, this is a slightly

modified T/F test. However, this strategy did not generate significant benefit

compared to participants who had not had to justify their choices (Schaap et

al., 2014). In attention to this, other modified experiments have required

undergraduates not to justify choices, but to correct false alternatives (Uner

et al., 2022).

Other modifications

experimented involved inserting competitive clauses into the statements, a

strategy that may make the tested information last longer in memory (Brabec et

al., 2021). For example, instead of the statement standing alone, there is

another statement inserted into it, in parentheses: Castle geyser (not Stemboat)

is the tallest geyser (example taken from the aforementioned paper).

It is relevant to

note that when students are prompted to correct alternatives which they think

are false, the presentation of feedback improves retention of correct

items on a subsequent short-answer test compared to a regular T/F procedure

(Uner et al., 2022). There are three types of feedback: the first, the right/wrong

feedback type; the second one, called corrective feedback, which

provides the student the correct answer; and the third one, called elaborate

feedback, which explains why a certain answer is true or false (Enders et

al., 2021).

Corrective feedback

can improve retention of tested items in T/F questions. Likewise, simple

modifications (such as inserting competitive clauses and requesting correction

of the wrong alternative or justification of the choice) in the way the test is

administered appear to be more effective and promising for classroom

implementation (Uner et al., 2022).

Regarding to

suggestions for writing T/F questions, here is what we

recommend to teachers: keep only one main idea in each alternative, and do not insert several of

them at the same time; make statements short and with understandable

vocabulary; avoid absolute terms (always, never, no one, etc.),

circumstantial modal words (can, maybe, sometimes, etc.), and double negatives (Santrock, 2009).

Multiple-choice

Multiple-choice (MC) questions

also involve answer selection. In terms of form, this type of question is

composed of two parts: the base (statement) and its set of possible answers, of

which only one is correct, and the others are lures (Santrock, 2009). MC

tests are often used by educators because, like T/F, they allow easier scoring

and are perceived as more objective (Butler et al., 2006). In fact, it is the

most used type of objective test (Marsh et al., 2007). In addition, MC quizzes

can be used throughout the school year to benefit student learning and

performance on final tests, whether they are MC (composed of recognition

questions) or short-answer (composed of elaboration questions) (McDermott et

al., 2014).

MC questions should be

worded so that lures are plausible (Little et al., 2012).

However, as already mentioned in the excerpt about T/F type questions, there is

the inconvenient effect of negative suggestion. Lures (incorrect answers) can be

learned and reproduced on a later test, so that the MC test can be

counterproductive if there are too many of them, as their interference can lead

to the assimilation of erroneous knowledge (e.g., Marsh et al., 2012a). Indeed,

an experiment conducted with undergraduates points out that

the greater the number of alternatives offered in the MC test, the less

beneficial the test is (Roediger & Marsh, 2005). In addition to the

interference caused by too many lures, insufficient study of the content prior

to the test contributes to the learning of misinformation (Butler &

Roediger, 2008).

To avoid negative

suggestion and leverage the benefits of MC tests, it is important to provide

feedback (Marsh et al., 2012a). Feedback, particularly corrective

feedback (in which the correct answer is given), is useful for correcting

misinformation that students have learned from lures, as well as for

maintaining long-term retention of correct answers (Butler, 2018).

MC tests were employed in

various research studies with different age, setting, and materials

employed. Experiments conducted with children (eight

years-old on average) show that they benefit from MC tests on general

knowledge, coupled with feedback (Marsh et al., 2012b). Other

experiments with teenagers (thirteen years-old on average) point out that

classroom science quizzes accompanied by feedback, even if they are brief,

increase students' performance on later summative assessments, whether MC or

short-answer (McDermott et al., 2014).

As for suggestions on how

to design MC questions, some general and some specific to this type of test can

be listed (Santrock, 2009; Butler, 2018). In general, MC questions should not

contain grammatical improprieties, should be understandable, are best written

as interrogative sentences, and should not contain tricky alternatives.

Specifically, they should have answers of similar length and alternate the

position of the correct alternatives between questions. It should be noted

again that the greater the number of alternatives, the lower the hit rate tends

to be (Butler et al., 2006). Moreover, MC tests should be appropriately

challenging, because if too easy or too difficult, they are useless for both

assessment and promotion of learning (Butler, 2018). A pertinent suggestion is to

affix the "I don't know" option, in order to avoid blind guessing

(Marsh et al., 2007). Again, the purpose of applying tests is learning, not

grading.

As stated earlier, among

its main disadvantages are the elaboration of

the alternatives (both in terms of number, format, and degree of difficulty)

and the possibility of negative suggestion (Butler, 2018). On the other hand,

this test format has the advantage of being easily verifiable. Thus, it

decreases the correction time and increases its objectivity (Butler et al.,

2006; Marsh et al., 2012a). Indeed, it can be applied throughout the school

year to boost learning (McDermott et al., 2014). Finally, marginal knowledge —

that is, the knowledge which, even though stored in memory, is not accessible

at any given time — can be easily reactivated through MC testing (Cantor et

al., 2015).

MC questions have,

therefore, important pedagogical implications, either in quizzes or in final

tests, as they are practical and economical, but require care in their preparation.

The recommendation to teachers, therefore, is to be

careful with the number of alternatives and try to elaborate clear questions

and plausible alternatives, with an adequate level of difficulty for the

students.

Short-answer

The

short-answer (SA) test format is widely used in the classroom. As can be

inferred from its name, it is the same as to answering questions with a short

answer. It is a test that imposes on the student to produce an answer (Larsen

et al., 2008). This type of test is similar to tests with cues. In this case,

however, the question is a cue that directs the respondent to the content to

remember (Moreira et al., 2019). For example, after studying key-term

definitions, 5th graders were asked to type in answers [e.g., What is sound?

____ (form of energy that you can hear and that travels through matter as

waves)] (Lipko-Speeda et al., 2014).

This test

format, like the free-recall test, requires more effort to remember and is more

difficult than the multiple-choice test format, which involves recognition

(Rowland, 2014). Effectively, research points out that SA tests are more

efficient at retaining content than multiple-choice tests (e.g., Kang et al.,

2007; Stenlund et al., 2016). However, there are studies that differ on this

point (see Little et al., 2012). Regarding this disagreement, it is important

to consider the age range of the students and the way the tests are formulated.

Tests should be designed so that students try to remember rather than just

identify answers (Little et al., 2012).

Several

studies with different educational levels have been conducted with the SA test

format, from elementary school (e.g., Goossens et al., 2016), through high

school (Dirkx et al., 2014), to undergraduation (e.g.,

Endres et al., 2020). These researches used as materials: book chapters (e.g.,

Carpenter et al., 2009), word lists (Goossens et al., 2016), key-concept

definition pairs (e.g., Lipko-Speeda et al, 2014),

expository texts (e.g., Dirkx et al., 2014), key-concepts of studied topics

(Wiklund-Hörnqvist et al., 2014), expository lectures (Foss & Pirozzolo,

2017), and lectures (Lyle & Crawford, 2011). Apart from the study by

Goossens et al. (2016), in all of the aforementioned studies there were

benefits of the short-answer test for learning.

Lipko-Speeda

et al. (2014) analyzed the effect of performing SA test with and without

feedback, employing rereading as a control condition. The target audience was

5th grade children, and the questions consisted of definitions of key-concepts

from Science and Geography content. Positive effects were seen only in the test

condition with feedback. In their study conducted with children, Goossens et

al. (2016) found that this test format without feedback was no better than copying the studied material.

Similarly, research conducted with high school students revealed that the SA

test with feedback, compared to rereading and administered after

studying a text on probability, increased retention of content from the text

and improved application of the principles covered in the text (Dirkx et al.,

2014).

Research

with undergraduates has pointed out that, compared to rereading, SA tests were

beneficial for long-term learning and retention (Larsen et al., 2009; Wiklund-Hörnqvist et al., 2014; Greving & Richter, 2018). A

study by Carpenter et al. (2016) showed that SA tests generated better results

with respect to recall of term definitions made by high-performing students.

However, for medium and low-performing students, copying term definitions was

better. In all these studies, feedback was offered after the initial SA

test, except for Greving and Richter's (2018) study. The latter evidenced that,

even without feedback, the short-answer test generated positive effects on

introductory Cognitive Psychology content.

SA tests

with feedback generate more learning outcomes (Kang et al., 2007). In this

sense, because this format involves more retrieval effort, one of the most

important precautions by teachers is to provide feedback with the correct

answers. Therefore, students can correct their mistakes instead of just knowing

what is right or wrong.

The

research cited earlier showed that CR tests with older students were more

efficient (e.g., Greving & Richter, 2018) than with younger students (e.g., Lipko-Speeda et al., 2014). It is therefore

recommended that to younger learners, cues are provided (see section below –

cued-recall) to facilitate recall. Another way out is to provide students with

more learning opportunities and tests until they can integrate and retain the

content (Lipko-Speeda et al., 2014).

One of the

benefits of SA questions is that they favor retention of specific points of a

content previously studied. Consequently, they facilitate the recall of more

difficult or inaccessible points. As an indirect effect, they allow

metacognitive accuracy, that is, the regulation of students' confidence in the

certainty of their answers and the proportion of answers given that they would

remember in a week. In this way, students' judgments regarding their learning

are more calibrated (accurate) in the SA format compared to the free-recall

test format (Endres et al., 2020). Another advantage is that conducting review

at the end of each class via SA questions encourages students to engage in

study and increases their performance on later tests (Greving & Richter,

2018).

One of the

disadvantages of SA quizzes are that, in practice, this format is not very

attractive to students. In addition, it can take teachers up to twice as long

to correct and apply it in class because the format requires more complex

answers (McDermott et al., 2014). However, it is not necessary to correct

individually, as the feedback can be collective (Butler & Roediger, 2007),

since the goal is learning, not grading based on student’s performance. Another

disadvantage concerns the fact that without feedback, or without further

study opportunities, such a format may not be as effective for retention of

information.

In

summary, SA tests are considered important for learning and recall, since

through this format, students can remember facts, definitions of key-concepts,

and specific content studied. Here is what we recommend to teachers: whenever

possible, provide feedback to make the integration of content more

effective.

Free-recall

Tests that

encourage free recall (FR) can

significantly boost new learning. Such a test format aims to search or

information and content that students have previously had access to in their

mind, without providing them with cues to get the correct answer (Brojde & Wise, 2008). An example is to ask students what

they remember about the topic "solar system".

FR tests

have shown beneficial results across different grade levels and age groups,

with children from two and a half years-old (Cornell et al., 1988), to

youngsters and adults (Tulving, 1967). However,

in the final test of the research conducted by Aslan and Bäuml

(2016), it was identified that younger children (six years-old on average) make

more mistakes when using FR to practice remembering. Older children (eight

years-old on average), on the other hand, benefit more from using FR testing (Aslan &

Bäuml, 2016).

As for the

settings of research on retrieval practice, considering only tests in FR

format, studies conducted in the participants' homes (Cornell et al., 1988), in

the laboratory (e.g., Lipowski et al., 2014), and at school in a classroom

setting (e.g., Jones et al., 2016) were observed.

Research

shows that, compared to rereading the same content, FR influences and enhances

processing in retrieving individual (Tulving, 1967) and specific items

(Lipowski et al., 2014). When comparing the effects of FR (retrieval practice)

with no test (Brojde & Wise, 2008; Roediger et al., 2011b) or with commonly

used study strategies such as copying (rewriting) (Jones et al, 2016; Rowley

& McCrudden, 2020) and rereading (Cornell et al., 1988; Aslan & Bäuml,

2016), it is observed that retrieval practice is one of the most effective

learning strategies that provides longer-lasting learning (Roediger et al.,

2011a). Thus, the advantages of using this type of test are that it enables

memory to be strengthened (Cornell et al., 1988), promotes understanding of the

content presented (Brojde & Wise, 2008), improves spelling accuracy (Jones

et al., 2016), and, as identified by Rohrer et al. (2010), stimulates the

transfer of information to new contexts, benefiting learning in a robust

manner.

In this

sense, FR tests show a direct testing-effect by pushing students to recall

information without cues being provided, thus stimulating desirable difficulty.

This especially benefits the learning of older children. Here is what we

recommend to teachers: provide opportunities for students to freely recall

content (e.g., ask students to write down or comment on what they remember

about the content studied in the previous lesson, without checking any note)

for students starting in elementary school.

Fill-in-the-blank

Fill-in-the-blank

test is a type of test that makes it possible to recall one or certain keywords

(Hinze & Wiley, 2011). For example, in Jaeger et al.'s (2015) study,

students completed sentences after studying a text about the Sun [e.g., The

word Sun is derived from the Latin word ________ (solis)].

This test

format is numerically the least explored in the literature. However, existing

studies have pointed out that this task makes it possible to retrieve items of

previously studied information. According to some studies, fill-in-the-blanks

can aid the retrieval of keywords from an encyclopedic text with 3rd graders

(Jaeger et al., 2015), English language vocabulary learning with 9th graders

(Barenberg et al., 2021), and item information about development, these

presented via PowerPoint to Psychology undergraduates (Vojdanoska et

al., 2010).

In Jaeger

et al.'s (2015) research, students who initially recalled with

fill-in-the-blank [e.g., The surface layer of the Sun is called ________

(photosphere)] - performed better on the final multiple-choice test

after seven days compared to students who reread the complete sentences. The

authors also argue that the practice of remembering through fill-in-the-blanks

can benefit children who perform differently in IQ (intellectual quotient) and

reading ability.

Barenberg

et al. (2021) conducted experiments with German and English word pairs. At

first, they administered the following fill-in-the-blank: a cue (German word)

and the target word (English word). After one week, students who underwent such

a test showed better results relative to those who underwent rereading, either

when they performed final test identical to the initial one, or when they did

it in reverse format (from target language to base language).

Feedback

was present in the research of Barenberg et al. (2021) and Vojdanoska et

al. (2010). The latter's results revealed that when feedback was provided, the

advantages of the test were magnified compared to testing without feedback and

without any activity.

One of the

positives of fill-in-the-blanks is that it is simple to apply in the classroom,

easy to correct, and not very time-consuming (Moreira et al., 2019). However,

there are indications that this format may not show high retrieval practice

effects. For example, in the experiment conducted by de Jonge et al. (2015),

undergraduates studied a text [coherent and noncoherent (isolated sentences)]

and performed a fill-in-the-blanks. As a control condition, rereading the

sentences was used. The authors concluded that the fill-in-the-blanks was more

beneficial for the noncoherent text format than for the coherent one. Thus,

this result may have stemmed from the fact that this type of task does not

require content integration and construction (Karpicke & Aue, 2015). In

other words, this type of task does not enable the student to meaningfully process

and develop more ideas, because its goal is to retrieve/retain one or a few

keywords.

Although

there are few studies investigating the application of this test format, it can

be observed, however, that fill-in-the-blanks presents a simple form of retrieval,

enabling learning to last longer. This format has also proven beneficial at

different levels of education, from elementary school to higher education

(Vojdanoska et al., 2010).

Cued-recall

Cued-recall

(CR) is a test format in which cues are provided to try to recall answers (Lima & Jaeger, 2020). For example, given a fill-in-the-blank

question, the first letter is provided to facilitate recall [e.g., The word

Sun derives from the Latin word s_______ (solis)] (Lima &

Jaeger, 2020). Other examples can be seen in the studies of Aslan and Bäuml

(2016), who used CR tests by presenting two to four initial letters of words

for students to complete noun lists. In turn, Kliegl et al. (2018) presented

blurry (unclear) versions of photos as a cue for students to associate them

with photos they initially studied.

Since it

provides cue to the response, CR facilitates retrieval of previously studied

information and increases the likelihood of retrieving information from memory

(Fazio & Agarwal, 2020). One possible explanation for this advantage is

that the benefits of retrieval practice are more robust when initial recall is

greater than 50% (Rowland, 2014).

CR tests

have been used as a teaching strategy with children as young as

two-years-and-ten-months-old (Fritz et al., 2007). As for settings, research

using cued-recall tests with has been conducted in school, in a classroom

setting (e.g., Ritchie et al., 2013), and individually, in a separate

room with the experimenter (imitating the laboratory setting) (e.g., Fritz et

al., 2007).

The

benefits of CR have already been demonstrated using everything from simple

materials — such as proper names (Fritz et al., 2007), names of sets of

taxonomic categories (i.e., categories that define groups of biological

organisms) and items, photos (with little pixel distortion) (Kliegl et al., 2018), fictional maps (Ritchie et

al., 2013), phrases and word lists with their synonyms (Goossens et al., 2014a)

— to more complex materials — such as sets of concept definition word-pairs

(Lipko-Speeda et al., 2014) and encyclopedic texts (Lima & Jaeger, 2020).

Ritchie et

al. (2013) identified that CR tests — taken based upon fictional maps that

featured the location of some cities as cues and asked students to try to

remember the name and its corresponding location on the maps — driven long-term

learning. On the downside, CR tests, when compared to

multiple-choice tests, resulted in lower recall. Still, both test formats

generate better performance compared to the content rereading condition (Lima & Jaeger,

2020).

The

benefits of CR testing are most robust when immediate feedback is provided

for preschool children (Kliegl et al., 2018). Regarding

undergraduates, CR tests followed by feedback comparing the easy

practice condition (in which the first two letters of the target word are

presented) to the hard practice condition (in which only the first letter of

the target word is presented) showed that mean retrieval performance was

significantly higher in the easy practice condition and in the short term.

However, one week later, performance in the hard practice condition was shown

to be superior (Kliegl et al., 2018). Thus, CR tests allow variation in

difficulty level and therefore adaptation of retrieval practice strategies

according to students' age group and prior knowledge (Fazio & Agarwal, 2020).

In short, the act of presenting cues while

performing retrieval practice can serve as an aid, thus increasing the

likelihood that students will arrive at the answers. Here is what we recommend to

teachers: when providing CR tests, vary the level of difficulty according

to students' prior knowledge, taking care not to make it too easy, but at the

same time pushing students to retrieve information.

Guidelines for educators

The

adaptability and applicability of retrieval practice via different test formats

allow educators and students to use different teaching (teacher-driven) and

study (student-driven) strategies (Roediger et al., 2011b; Agarwal et al.,

2018). There are a variety of question types and test formats that can be used

in real classroom settings (McDaniel et al., 2013) in order to benefit learning

in flexible ways (McDaniel et al., 2013; Agarwal et al., 2018).

To

facilitate the use of retrieval practice, a "retrieval practice

guide" (Agarwal et al., 2018) and numerous

research (e.g., Ekuni & Pompeia, 2020) present

suggestions as well as guidelines for educators to use and encourage the

performance of retrieval practice in the course of the teaching and learning

process. From the research findings presented in this review, we will provide a

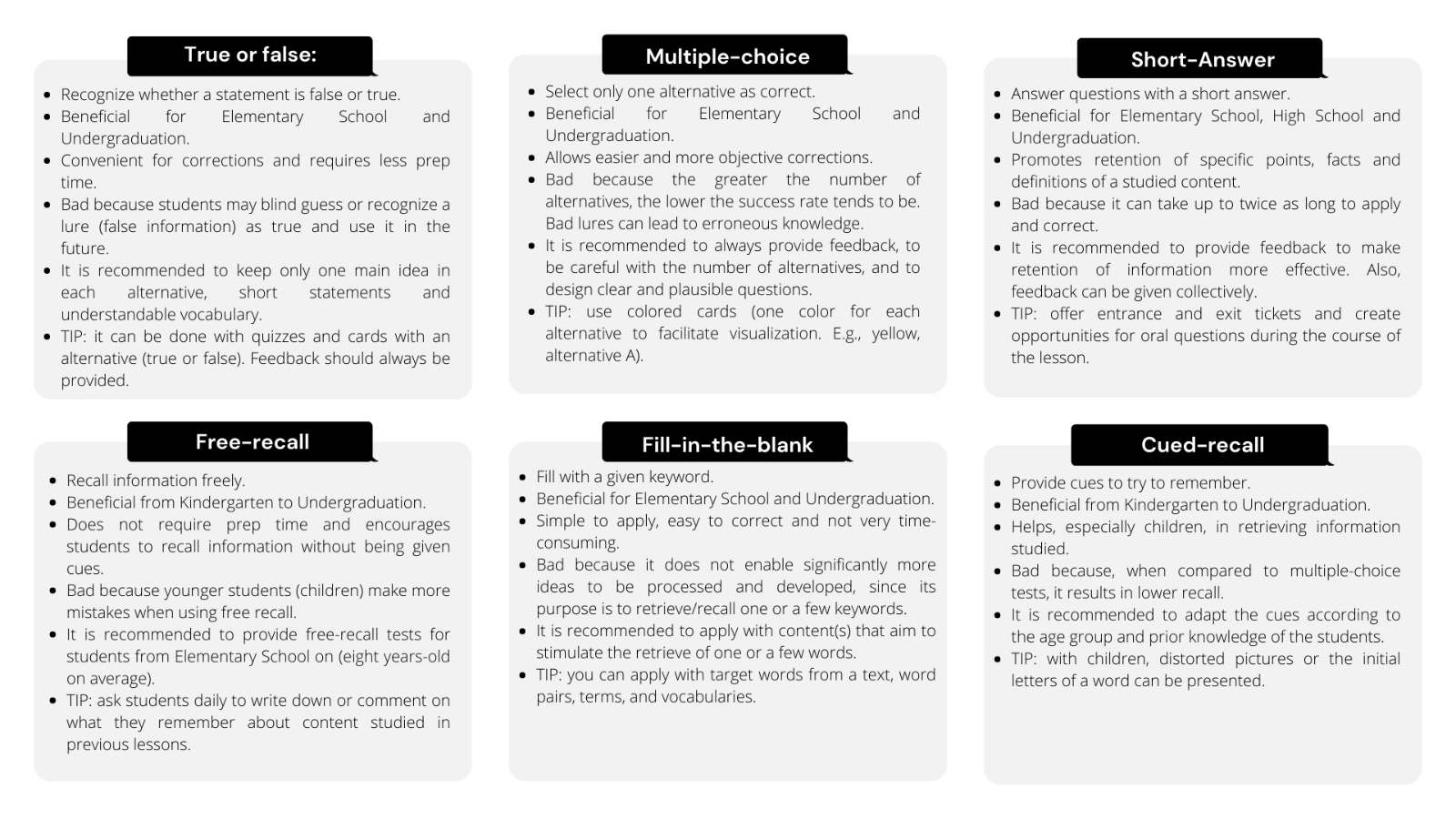

summary with the main guidelines (see Image 1).

When using

retrieval practice, students need to be guided that during testing, they should

not consult materials, notes, or even their peers

(Agarwal et al., 2018). They should be honest, searching their minds for

information they have previously accessed (Agarwal et al., 2018). One way to

encourage the whole class to practice retrieval is to be cautious when

directing questions. The teacher might, for example, ask an oral question, give

students some time to think about the answer, and only then draw names of

students to answer aloud.

Image 1

Comparison chart of the studies presented with test formats and

recommendations to educators.

Source: made by the authors.

True-false

and multiple-choice tests can be addressed in real time from quizzes (Agarwal

et al., 2013). One idea is to use colored cards (like little signs) for

students to raise their answer at the teacher's command. It is even better if

the cards have standardized colors, so as to maintain the correspondence

between colors and alternatives (Agarwal et al., 2013; Ekuni & Pompeia,

2020) (e.g., the card with the TRUE alternative can be white, and with the

FALSE alternative, red; with respect to alternatives from A to D, the guidance

is to use different colored cards as well, such as yellow for alternative A,

blue for B, and so on). This way it is easy to visualize the alternatives most

chosen by the students. When asking a question (by voice, by projection on

screen, or by writing on the blackboard), you should give the students time to

think about the answer before asking them to raise their cards. To further

increase the benefit, feedback should be provided (e.g., Agarwal et al., 2018;

Ekuni & Pompeia, 2020).

Strategies

related to short-answer and free-recall tests can be put into practice with

entrance and exit tickets (McDermott et al., 2014; Agarwal et al., 2018). This

strategy can be accomplished using pieces of notebook paper, or bond paper. As

students enter the classroom, the teacher can hand out the pieces of paper and

ask, for example, for students to write down what they remember from the

previous lesson. With exit tickets, it is possible to ask that, before the end

of the lesson, students write down, for example, what they found most

interesting about the topic covered (Agarwal et al., 2018).

Still

considering free-recall tests, it is possible for the teacher to ask the

students to make an oral or written summary of the content previously presented

(Brojde & Wise, 2008). The teacher can also perform dictations with the

goal of having students recall the spelling of words, meanings, and definitions.

Free-recall tests can also be stimulated through interventions during readings

in which the child is asked to point to pictures in the book (Cornell et al.,

1988). Students can also be required to write a list of previously presented

words in a dictation (Jones et al., 2016), or to write down everything they

remember about a previously studied text (Rowley & McCrudden, 2020).

Regarding

fill-in-the-blanks tests, it is possible to use them based on target words

highlighted in a text. At the time of the test, you can present the definition

so that students try to remember and fill in with the target word (Goossens et

al., 2014b). In fill-in-the-blanks tests, one can practice retrieval using

pairs of associated words, matching terms with words, etc. (e.g., suburb and

outskirts - suburb and ________).

In

cued-recall tests, one can present somewhat distorted images as cues and then

ask students to name them (Kliegl et al., 2018). One

can study phrases or lists of associated words and, at test time, provide one

or two letters of the target word for students to try to remember and write the

whole word (Kliegl et al., 2019).

There are,

therefore, numerous possibilities to diversify the choice of test format when

practicing retrieving. It is important to consider that different test formats

benefit learning (McDermott et al., 2014; Agarwal et al., 2018). Furthermore,

offering feedback after practice can help students correct errors and encourage

retention of correct information (Marsh et al., 2012b). It is important to

provide testing not only for the purpose of assessment or grading, but as a

teaching strategy.

Conclusion

In view of an education based

on scientific evidence, the present review points out different ways and test

formats for implementing retrieval practice in a classroom setting. This makes

it possible to contribute significantly to long-lasting and flexible learning.

The results of the studies generally show that each format can contribute

effectively to different content, materials, and grade levels. However, the

present review, by being narrative, has limitations regarding the selection of

papers. Future studies may conduct a systematic review on the theme, by

conducting systematic searches.

From this research, it is

also observed that the age of the students and the level of education seem to

play an important role in the choice and implementation of the test format.

With younger students, providing cues during retrieve may be more effective for

learning. With older students, on the other hand, tests with a higher desirable

difficulty can be provided. Another point concerns feedback. When given,

whatever the test format is, it improves retention and corrects errors.

Therefore, the effects of retrieval practice in an educational setting are

robust. For these and other reasons, retrieval practice is a promising strategy

for teaching and learning for students of different age groups.

Abbott, E. E. (1909). On the analysis of the factor of recall in the

learning process. Psychological Review: Monograph Supplements, 11(1),

159-177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093018

Agarwal, P. K., &

Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful Teaching: unleash the science of learning.

Jossey-Bass.

Agarwal, P. K.,

D’Antonio, L., Roediger, H. L., McDermott, K. B., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014).

Classroom-based programs of retrieval practice reduce middle schooland high

school students’ test anxiety. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and

Cognition, 3(3), 131-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.07.002

Agarwal, P. K., Roediger,

H. L., McDaniel, M. A., & McDermott, K. B. (2013). How to use retrieval

practice to improve learning [E-book]. Washington University in St. Louis. https://www.retrievalpractice.org/library

Agarwal, P. K., Roediger,

H. L., McDaniel, M. A., & McDermott, K. B. (2018). Como a Prática de Lembrar pode ser utilizada para

melhorar a aprendizagem [E-book]. Washington University in

St. Louis. https://www.retrievalpractice.org/library

Aslan, A., & Bäuml, K.

H. T. (2016). Testing enhances subsequent learning in older but not in younger

elementary school children. Developmental Science, 19(6),

992–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12340

Barenberg, J., & Dutke,

S. (2019). Testing and metacognition: retrieval practise effects on

metacognitive monitoring in learning from text. Memory, 27(3),

269-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2018.1506481

Barenberg, J., Berse, T.,

Reimann, L., & Dutke, S. (2021). Testing and transfer: Retrieval practice

effects across test formats in English vocabulary learning in school. Applied

Cognitive Psychology, 35(3), 700-710. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3796

Bjork, R. A. (1975).

Retrieval as a Memory Modifier: an interpretation of negative recency and

related phenomena. Em R. L. Solso (Ed.). Information processing and

cognition: The Loyola Symposium (pp. 123-144). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brabec, J. A., Pan, S.

C., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2021). True-False Testing on Trial:

Guilty as Charged or Falsely Accused? Educational Psychology Review, 33(2),

667-692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09546-w

Brojde, C. L., &

Wise, B. W. (2008). An Evaluation of the Testing Effect with Third Grade

Students. Proceedings of the 3-Th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science

Society, 1362-1367.

Butler, A. C. (2018). Multiple-Choice Testing in Education: Are the Best

Practices for Assessment Also Good for Learning? Journal of Applied Research

in Memory and Cognition, 7(3), 323-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.07.002

Butler, A. C., &

Roediger, H. L. (2007). Testing improves long-term retention in a simulated

classroom setting. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4-5),

514-527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440701326097

Butler, A. C., &

Roediger, H. L. (2008). Feedback enhances the positive effects and reduces the

negative effects of multiple-choice testing. Memory and Cognition, 36(3),

604-616. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.36.3.604

Butler, A. C., Marsh, E.

J., Goode, M. K., & Roediger, H. L. (2006). When additional multiple-choice

lures aid versus hinder later memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(7),

941-956. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1239

Cantor, A. D., Eslick, A.

N., Marsh, E. J., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2015). Multiple-choice

tests stabilize access to marginal knowledge. Memory & Cognition, 43(2),

193-205. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-014-0462-6

Carpenter, S. K. (2011).

Semantic Information Activated During Retrieval Contributes to Later Retention:

Support for the Mediator Effectiveness Hypothesis of the Testing Effect. Journal

of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 37(6),

1547-1552. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024140

Carpenter, S. K., Lund, T.

J. S., Coffman, C. R., Armstrong, P. I., Lamm, M. H., & Reason, R. D.

(2016). A Classroom Study on the Relationship Between Student Achievement and

Retrieval-Enhanced Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2),

353-375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9311-9

Carpenter, S. K.,

Pashler, H., & Cepeda, N. J. (2009). Using tests to enhance 8th grade

students’ retention of U.S. history facts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(6),

760-771. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1507

Collins, A. J., & Fauser, C. J. M. B.

(2005). Balancing the strengths of systematic and narrative reviews. Human

Reproduction Update, 11 (2),103-104. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmh058

Cornell, E. H., Sénéchll,

M., & Broda, L. S. (1988). Recall of Picture Books by 3-Year-Old Children:

Testing and Repetition Effects in Joint Reading Activities. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 80(4), 537-542. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.4.537

de Jonge, M., Tabbers, H.

K., & Rikers, R. M. J. P. (2015). The Effect of Testing on the Retention of

Coherent and Incoherent Text Material. Educational Psychology Review, 27(2),

305-315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9300-z

Dirkx, K. J. H., Kester,

L., & Kirschner, P. A. (2014). The testing effect for learning principles

and procedures from texts. Journal of Educational Research, 107(5),

357-364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.823370

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.

A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving

students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions

from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the

Public Interest, Supplement, 14(1), 4-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Ekuni,

R., & Pompeia, S. (2020). Prática De Lembrar: a Quais Fatores Os Educadores

Devem Se Atentar? Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 24, e220284. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-35392020220284

Ekuni, R., Souza, B. M. N., Agarwal, P. K., & Pompeia, S. (2020). A

conceptual replication of survey research on study strategies in a diverse,

non- WEIRD student population. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in

Psychology, Advance online publication, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000191

Elias, C. D. S.

R., da Silva, L. A., Martins, M. T. D. S. L., Ramos, N. A. P., de Souza, M. D.

G. G., & Hipólito, R. L. (2012). Quando chega o fim? Uma revisão narrativa

sobre terminalidade do período escolar para alunos deficientes mentais. SMAD, Revista

Electrónica en Salud Mental, Alcohol y Drogas, 8(1), 48-53. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1806-6976.v8i1p48-53

Enders, N., Gaschler, R.,

& Kubik, V. (2021). Online Quizzes with Closed Questions in Formal

Assessment: How Elaborate Feedback can Promote Learning. Psychology Learning

and Teaching, 20(1), 91-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725720971205

Endres, T., Kranzdorf,

L., Schneider, V., & Renkl, A. (2020). It matters how to recall – task

differences in retrieval practice. Instructional Science, 48(6),

699-728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-020-09526-1

Fazio, L. K., &

Agarwal, P. K. (2020). How To Implement Retrieval-Based Learning in Early

Childhood [E-book]. Washington University in St. Louis. https://www.retrievalpractice.org/library

Foss, D. J., &

Pirozzolo, J. W. (2017). Four semesters investigating frequency of testing, the

testing effect, and transfer of training. Journal of Educational Psychology,

109(8), 1067-1083. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000197

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P.

E., Nolan, D., & Singleton, J. (2007). Expanding retrieval practice: An

effective aid to preschool children’s learning. Quarterly Journal of

Experimental Psychology, 60(7), 991-1004. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210600823595

Goossens, N. A. M. C.,

Camp, G., Verkoeijen, P. P. J. L., & Tabbers, H. K. (2014a). The effect of

retrieval practice in primary school vocabulary learning. Applied Cognitive

Psychology, 28(1), 135-142. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2956

Goossens, N. A. M. C.,

Camp, G., Verkoeijen, P. P. J. L., Tabbers, H. K., & Zwaan, R. A. (2014b).

The benefit of retrieval practice over elaborative restudy in primary school

vocabulary learning. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition,

3(3), 177-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.05.003

Goossens, N. A. M. C.,

Camp, G., Verkoeijen, P. P. J. L., Tabbers, H. K., Bouwmeester, S., &

Zwaan, R. A. (2016). Distributed Practice and Retrieval Practice in Primary

School Vocabulary Learning: A Multi-classroom Study. Applied Cognitive

Psychology, 30(5), 700-712. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3245

Greving, S., &

Richter, T. (2018). Examining the testing effect in university teaching:

Retrievability and question format matter. Frontiers in Psychology, 9,

02412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02412

Hinze, S. R., &

Wiley, J. (2011). Testing the limits of testing effects using completion tests.

Memory, 19(3), 290-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.560121

Jaeger, A., Eisenkraemer,

R. E., & Stein, L. M. (2015). Test-enhanced learning in third-grade

children. Educational Psychology, 35(4), 513-521. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.963030

Jones, A. C., Wardlow,

L., Pan, S. C., Zepeda, C., Heyman, G. D., Dunlosky, J., & Rickard, T. C.

(2016). Beyond the Rainbow: Retrieval Practice Leads to Better Spelling than

does Rainbow Writing. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2),

385-400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9330-6

Kang, S. H. K.,

McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2007). Test format and corrective

feedback modify the effect of testing on long-term retention. European

Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4-5), 528-558. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440601056620

Karpicke, J. D., &

Aue, W. R. (2015). The Testing Effect Is Alive and Well with Complex Materials.

Educational Psychology Review, 27(2), 317-326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9309-3

Karpicke, J. D., Blunt,

J. R., Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, S. S. (2014). Retrieval-based learning:

The need for guided retrieval in elementary school children. Journal of

Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(3), 198-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.07.008

Karpicke, J. D., Butler,

A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in student

learning: Do students practise retrieval when they study on their own? Memory,

17(4), 471-479. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210802647009

Kliegl, O., Abel, M.,

& Bäuml, K. H. T. (2018). A (preliminary) recipe for obtaining a testing

effect in preschool children: Two critical ingredients. Frontiers in

Psychology, 9, 01446. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01446

Kliegl, O., Bjork, R. A.,

& Bäuml, K. H. T. (2019). Feedback at test can reverse the retrieval-effort

effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01863

Larsen, D. P., Butler, A.

C., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). Test-enhanced learning in medical education. Medical

Education, 42(10), 959-966. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03124.x

Larsen, D. P., Butler, A.

C., & Roediger, H. L. (2009). Repeated testing improves long-term retention

relative to repeated study: A randomised controlled trial. Medical

Education, 43(12), 1174-1181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03518.x

Lima, N. K. de, &

Jaeger, A. (2020). The Effects of Prequestions versus Postquestions on Memory

Retention in Children. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition,

9(4), 555-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.08.005

Lipko-Speeda, A.,

Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2014). Does testing with feedback help

grade-school children learn key concepts in science? Journal of Applied

Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(3), 171-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.04.002

Lipowski, S. L., Pyc, M.

A., Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2014). Establishing and explaining the

testing effect in free recall for young children. Developmental Psychology,

50(4), 994-1000. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035202

Little, J. L., Bjork, E.

L., Bjork, R. A., & Angello, G. (2012). Multiple-Choice Tests Exonerated,

at Least of Some Charges: Fostering Test-Induced Learning and Avoiding

Test-Induced Forgetting. Psychological Science, 23(11),

1337-1344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612443370

Lyle, K. B., &

Crawford, N. A. (2011). Retrieving Essential Material at the End of Lectures

Improves Performance on Statistics Exams. Teaching of Psychology, 38(2),

94-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628311401587

Marsh, E. J., Fazio, L.

K., & Goswick, A. E. (2012b). Memorial consequences of testing school-aged

children. Memory, 20(8), 899-906. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.708757

Marsh, E. J., Lozito, J.

P., Umanath, S., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2012a). Using verification

feedback to correct errors made on a multiple-choice test. Memory, 20(6),

645-653. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2012.684882

Marsh, E. J., Roediger,

H. L., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2007). The memorial consequences of

multiple-choice testing. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2),

194-199. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194051

McDaniel, M. A., Thomas,

R. C., Agarwal, P. K., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2013). Quizzing

in Middle-School Science: Successful Transfer Performance on Classroom Exams. Applied

Cognitive Psychology, 27(3), 360-372. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2914

McDermott, K. B. (2021).

Practicing Retrieval Facilitates Learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 72,

609-633. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-051019

McDermott, K. B., Agarwal,

P. K., D’Antonio, L., Roediger, H. L. I., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Both

multiple-choice and short-answer quizzes enhance later exam performance in

middle and high school classes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied,

20(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000004

Moreira, B. F. T., Pinto,

T. S. da S., Justi, F. R. R., & Jaeger, A. (2019). Retrieval practice

improves learning in children with diverse visual word recognition skills. Memory,

27(10), 1423-1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2019.1668017

Ritchie, S. J., Della

Sala, S., & McIntosh, R. D. (2013). Retrieval practice, with or without

mind mapping, boosts fact learning in primary school children. PLoS ONE,

8(11), e78976. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078976

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006a). Test-Enhanced Learning:

Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science,

17(3), 249-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

Roediger, H. L., &

Karpicke, J. D. (2006b). The Power of Testing Memory: Basic Research and

Implications for Educational Practice. Perspectives on Psychological Science,

1(3), 181-210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x

Roediger, H. L., &

Karpicke, J. D. (2011). Intricacies of Spaced Retrieval: A resolution. Em A. S.

Benjamin (Ed.). Successful Remembering and Successful Forgetting: a

festschrift in honor of Robert A. Bjork. (pp. 70-115). Taylor and Francis

Group.

Roediger, H. L., &

Marsh, E. J. (2005). The Positive and Negative Consequences of Multiple-Choice

Testing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition,

31(5), 1155-1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.31.5.1155

Roediger,

H. L., & Pyc, M. A. (2012). Inexpensive techniques to improve

education: Applying cognitive psychology to enhance educational practice. Journal

of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(4), 242-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2012.09.002

Roediger, H. L., Agarwal,

P. K., McDaniel, M. A., & McDermott, K. B. (2011b). Test-Enhanced Learning

in the Classroom: Long-Term Improvements From Quizzing. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(4), 382-395

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026252

Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith,

M. A. (2011a). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational

practice. Em J. P. Mestre & B. R. Ross. The psychology of learning and

motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 1-36). Elsevier Academic Press.

Rohrer, D., Taylor, K.,

& Sholar, B. (2010). Tests Enhance the Transfer of Learning. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 36(1),

233-239. https:/doi.org/10.1037/a0017678

Rother, E. T. (2007). Revisión sistemática X

Revisión narrativa. Acta paulista de enfermagem, 20, v-vi. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21002007000200001

Rowland, C. A. (2014). The

effect of testing versus restudy on retention: a meta-analytic review of the

testing effect. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1432-1463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037559

Rowley, T., &

McCrudden, M. T. (2020). Retrieval practice and retention of course content in

a middle school science classroom. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(6),

1510-1515. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3710

Santrock, J. W. (2009). Psicologia

Educacional. McGraw-Hill.

Schaap, L., Verkoeijen,

P., & Schmidt, H. (2014). Effects of different types of true-false

questions on memory awareness and long-term retention. Assessment and

Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(5), 625-640. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.860422

Slavin, R. E. (2020). How

evidence-based reform will transform research and practice in education. Educational

Psychologist, 55(1), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1611432

Stenlund, T., Sundström,

A., & Jonsson, B. (2016). Effects of repeated testing on short- and

long-term memory performance across different test formats. Educational Psychology,

36(10), 1710-1727. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.953037

Tulving, E. (1967). The

effects of presentation and recall of material in free-recall learning. Journal

of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6(2), 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80092-6

Uner, O., Tekin, E.,

Roediger, H. L. (2022). True–false tests enhance retention relative to

rereading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 28(1),

114-129. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000363

Van den Broek, G.,

Takashima, A., Wiklund-Hörnqvist, C., Wirebring, L. K., Segers, E., Verhoeven,

L., & Nyberg, L. (2016). Neurocognitive

mechanisms of the “testing effect:" A review. Trends in Neuroscience

and Education, 5(2), 52-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2016.05.001

Vojdanoska, M., Cranney,

J., & Newell, B. R. (2010). The testing effect: The role of feedback and

collaboration in a tertiary classroom setting. Applied Cognitive Psychology,

24(8), 1183-1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1630

Wiklund-Hörnqvist, C.,

Jonsson, B., & Nyberg, L. (2014). Strengthening concept learning by

repeated testing. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(1),

10-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12093

Yang, C., Luo, L.,

Vadillo, M. A., Yu, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2021). Testing (quizzing) boosts

classroom learning: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Psychological

Bulletin, 147(4), 399-435. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000309